|

(About an 18-minute read)

Are there benefits to 'long-form' team building activities?

If you've been around the OnTeamBuilding (ideas) and FUNdoing (activities) for a while, you know I like to take deep dives into ideas and activities. Over the last two years in particular I've been encouraging team builders to revisit the concept of 'less is more' and to consider a Stoic practice of 'do less better.' Think about these two ideas for just a moment. What do they mean to you? Less is more. Do less better.

I know, and have lived the argument, that if we do a lot of activities we have done a lot and can justify our time together with our clients - we gave them 'a lot' for their money. (Have you ever been in that position where you want to get that "one more" activity in and then you run out of time to reflect over the program in a meaningful way? So then it's, "Oh, we have time for the 'One Word' Whip." I've been there. I've done the Whip. And what did I miss? What did my clients miss?)

I'm sure you can see where I'm going with this? Before we continue the exploration, let me frame my thinking about activity 'form' (in other words, the length of time it usually takes to go through an activity). I've recently begun using the terms 'long-form,' 'short-form,' and 'mid-form' activities when talking about program design with team builders (it sounds more methodological). Long- and short-form are common terms in journalism, blogging and publishing. Mid-form I made up to designate an amount of time between long and short. In my mental model, short-form activities take 10 to 15 minutes (e.g., energizers and warm ups). Mid-form activities take 20 to 50 minutes. And long-form activities can take 60 minutes or more.

As I mentioned above, we are very familiar with short-form and mid-form activities. We like 'changing it up' to keep everyone's attention and meet different learning styles and 'kinds of smarts' - the more we change it, the more people we can connect with - so the argument goes. And it's a good argument. And it works. And what else can we do? I'm suggesting here, more long-form programming. How about an example? I invited my friend and colleague Bill (Ph.D.) into my "College is an Adventure" course when I was teaching in higher ed. (The course was for college freshman - I taught college success strategies using team building activities.) I heard about his multiple-session "Swing-To" activity and wanted to learn how to facilitate it. He joined us for three 50-minute class periods and it was well worth the time. The experience was, without a doubt, a genuine example (metaphorically speaking) of getting through college. The Swing-To is a version of 'Prouty's Landing' - a swinging rope to a platform activity. Bill used Hula-Hoops as safe landing areas and the apex of our swinging rope was about 25 feet high which gave us a lot of room to swing. The goal was the same for each of his three meetings, "Get everyone into a hoop. Each hoop needed at least one person in it." The only way to get into a hoop was to swing.

The insights these students had and the connections/transfers they made to life as a college student was exactly why Bill designed Swing To. And designing it to take a long time was on purpose. It takes a while to 'get it' - challenges in life are not always in short-form. It's good to practice for the long-form challenges every now and then.

I left out a number of the finer details of the activity, but I hope you can see my intent. Over those three classes, think about the 'obstacles' the students had to navigate. Just like college. Think about how they evolved into a group to achieve more success on one particular goal. How does this relate to college? (It's much harder to do it alone.) What are all the things they had to overcome. What was ahead of them, what did they need to overcome throughout their years in college. How long does it take to 'see' and 'feel' what's possible? Can we help our learners practice what it takes? Which leads me to my current interest in long-form team (human) building activities.

Concepts we can dive into with long-form activities:

Long-Form Activity Ideas:

I'd love to add more activities to my long-form list - what do you/would you do in long-form? Please share in the Comments.

If you made it this far, you just experienced a long-form blog post. Worth it? Waist of time? Benefits? Drawbacks? Did it make you think or roll your eyes? Both? Needed? For what? Keep doing the good work out there! All the best, Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

P.S. Would you like a super-quick update when new OnTeamBuilding content is posted? Just fill out the form below and then click the big blue button. I'll keep you posted.

2 Comments

(About a 10-minute read. This is a migration and updated post. It was first shared at the FUNdoing.com Blog. We are moving theoretical posts to OnTeamBuidling in an effort to organize content. Thanks for being here!)

Fast Ball is published in, Portable Teambuilding Activities (Cavert, 2015). (I've also posted the full description at the FUNdoing Blog site.) It's a challenging "mental model" activity where groups initially define (via Groupthink) a word (or direction) in one way and in order to be more successful they need to redefine something to break through a barrier or problem. (One of the strategies to innovate is to redefine something you believe is true in order to discover a more beneficial solution.)

After using this activity a few times, Jeremy, a fellow FUN Follower (and good friend) wrote me, asking: I have a question for you about the game Fastball. I have facilitated this activity mostly with college and adult groups and it does tend to take a while 30 min – 1 hr. for groups to complete. When the group finally gets it and is able to complete the challenge, there has been a common reaction of great let down and almost the look from participants like “You tricked us”. How have you led this activity so that it does not take so long that group members check out or become so frustrated by the end? It doesn’t bother me to frustrate a group or to raise the tension, but I’ve found it hard to bring the processing back around and be productive because the group is just done with it. Early on in my team building career, I struggled with this same issue when learning about and working with activities like Fast Ball. (Group Juggle to Warp Speed comes to mind - you create a tossing "order" standing in a circle but remaining in a circle is not a rule - forming a line in the same tossing order can lead to a faster time.) I tend to lead activities like this with adult groups (college age or older) in one of three ways: 1) When I have time (like Jeremy) I let the activity play out until the shift is made. And, as Jeremy found out, it can take up to an hour. I have experienced group reactions of success and powerful learnings, and frustration and projected blame on me, their facilitator. (Lots to talk about in both situations.) There have been times during the 'blaming' reaction where the group felt tricked and it was difficult to get them to focus back on any learnings that could be surfaced. These groups were not ready to see the learning(s) underneath the challenge. I'm sure I did my best, at the time, to move forward, but these (or any) reactions cannot be predicted. We do the best we can to program activities that will meet the objectives of our groups. (Here is another interesting topic to explore at another time: What are some strategies to bring a group "back" from a "negative" experience?)

2) Here is the way I lead Fast Ball most of the time (mostly because I don't have the time to let this play out). I frontload the activity with some information that might move the group to the shift in thinking quicker. I tell them:

"On the surface, this activity might seem relatively easy to accomplish. And it could be. You might "get it" right away. However, I've seen a lot of groups struggle with this one for one reason or another. The activity is designed to make you think. Remember, when approaching a challenge or task be mindful of the "problems" you encounter. Solve one problem at a time and keep moving. If you reach an impasse see this as an opportunity to be creative and innovative. I will hold you accountable to the rules and you are free to clarify my expectations about them at any time." After this frontload I let them play. I usually will remind them of some of the points in the frontload when they seem to be "stuck" - but for the most part, groups will make the shift and produce their fastest time within 30 minutes.

3) When I program experiences involving objectives related to mental models, paradigms, phantom rules, or simply making assumptions, I will use Fast Ball as one experience of many, to touch on the learning points. I will move into the "Educator as Teacher" role from time-to-time. I will ask more pointed questions like:

Depending on your experiential philosophy, asking these types of questions will not be your preference. As I've learned, there are a wide range of tools we can use, as educators, to reach our objectives (i.e., the objectives you have for the group or the objectives a group brings with them), other than giving a group the answers (there is less experiential learning in this method, but it could serve a purpose from time-to-time). However, I don't want to limit the tools at my disposal. Again, if I choose to point the group in a direction with Fast Ball (or another other mental model activity), it is by design. I've planned a number of these 'shifty' activities with the hope that my groups will move to different ways of defining and thinking on their own - a skill or behavior I want them to pick up and practice. A BIG thanks to Jeremy for sending me the inquiry. I hope I've provided some insight. Let me know what you thinking about these approaches. Leave a Comment below. All the best, Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

P.S. Would you like a super-quick update when new OnTeamBuilding content is posted? Just fill out the form below and then click the big blue button. I'll keep you posted.

(About a 12-minute read - plus a little thinking time if you have some. This is a migration and updated post. It was first shared at the FUNdoing.com Blog. We are moving theoretical posts to OnTeamBuidling in an effort to organize content. Thanks for being here!)

Preface: This post is a bit of a journey. And if I may say so, an important one. It relates to diversity. Diversity is never going away - nor should it. We need it. I'm guessing you've heard this before, "Diversity makes us stronger!" The challenge is (and this is where team builders can help), we have to do some work, to make it work. Grab a warm beverage and let's dive in...

I received this question from a fellow team builder, let's call him John:

John: I was wondering if you have come across/created any activities for groups that are interested in exploring generational issues/awareness? (I didn't have any specific activities to share with John, but I countered with a question and some reflection.) Chris: John, let me ask you this: What problems (or concepts) do you want to dive into with such activities? (I have a pretty good idea, but I'm interested in your perspective.) When I know what I'm working on, or towards, it's easier for me to find activities that may surface the desired behaviors and outcomes. I've had clients in the past expressing concern over the dynamics between the "older" and "newer" (i.e., younger) employees. When I worked with them, we explored the behaviors that were showing up (things seen and heard) during the program activities. I would ask which behaviors were working for them and which ones where not? Then, it was all about deciding what the group wanted to keep doing and what they wanted to change (or start doing). Some behaviors (good or bad) did relate to different ways of thinking, which could have been attributed to generational differences - but is that the REAL issue? From my point of view, it's about diversity.

John, you and I know diversity is an important topic in the workplace and in educational settings around the world. Age gaps (that might include different ways of thinking, acting and being) are, as I have experienced, diverse groups of people challenged to find ways to work together.

Thoughts?

John: I am not trying to solve any problem per se. I look at generational stuff as generational intelligence, like emotional intelligence with four categories:

1. self-awareness 2. self-management 3. social awareness 4. social management [Note from Chris: See the CASEL website for more on EI.] I would like to raise "generational intelligence." [from Chris: I love this term!] Is all this generational stuff just different behaviors as you mentioned? Is it different cultural dimensions? Is it a hoax? Or is it more? My leaning is toward more. I've worked with groups (7th graders, MBA students, etc.) for decades. I am getting older, and they remain the same age. So, it could be me being different/older but I see a difference in these groups. For one, they all seem nicer. And less strategic. And they jump to a solution...I call this firing...and they keep on firing without any sense of ready or aim (their world is one of velocity). They also do not seem strategically interested in going in a straight line from A to B and would rather go out in some tangential direction away from B but thinking that it still leads to B (don't know if I am clear here?). Do you see any of this?

So, I am big on raising awareness and managing that new awareness for a different result.

I was recently taught two new words. Ethnocentric (believing that your way is the only way or the best way) and ethnorelative (believing that there are many ways/thoughts/cultural preferences which are different than yours yet valid and important for you to master in order to be a great leader). This has changed my thinking immensely. My awareness and management of self and others has shifted because of this. I have moved away from binary thinking to dialectic (AND)...that multiple ways are both/all right. I would like to investigate generational issues with the same light. I am not a researcher [but I do] like to test things and collect data. Which ties into the experiential activity field we are in. Why not divide groups by generations and see how they solve problems/think? Is there any correlation across generations? Reflecting on my observations, people from different generations seem to look at each other as if they were aliens. How to shine light here?

Chris: It just so happens that (based on a recommendation from Michael Cardus) I started reading the book, Helping: How to Offer, Give, and Receive Help (2009) by Edgar Schein. So far, it's been an engaging read since I can correlate a lot of the teambuilding I do directly to helping behaviors. Here are a few points from the first two sections of the book that, I believe, can relate to our generational issues/awareness discussion:

This social economics concept (or social theory) struck a chord with me in relation to generational issues/awareness. Let's consider a group of multi-generational participants (e.g., co-workers). If one generation thinks ethnocentrically and the other thinks ethnorelatively the communication between the generations may not mesh with the social economics expectations of each generation thus causing friction.

I'm sure it's also possible for two different generations within a group to be the same types of thinkers. What if both groups (generations) had an ethnocentric point of view - each thought their way was the best way. How would we work with that situation (or those behaviors)? What if both generations were ethnorelative thinkers? Maybe the group doesn't have any problems? (Other than maybe, deciding what to do because everyone has a good idea!) Questions arise: How do we know what kind of thinkers we're working with? Is this about generational issues or is it about diversity? Where do you choose to focus?

For reasons of time, my conversation with John is on hold - but still on the table. I am grateful for his inquiry and the conversation. Our thinking helps us expand our understandings. Do we ever find the answers? Sometimes. At other times we just need to keep talking, staying in dialogue with the curious.

I'd like to invite you into a little reflection:

It's easy to understand this discussion of generational awareness and the work we do to foster its awareness is an ongoing journey. For now, I'd like to let these ideas take some hold and see how they grow. Discussions or dialogues like this can help us learn and grow in ways we might have never considered. I believe it's vital to bring up the questions that matter to us and engage in conversations with 'like' and 'other' perspectives to gain deeper understanding of different points of view and the people who carry them. I believe this to be true: It's not about against, it's about together. How do we help make this happen?

Please, keep doing the good work. We need you!

All the best, Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

P.S. Would you like a super-quick update when new OnTeamBuilding content is posted? Just fill out the form below and then click the big blue button. I'll keep you posted.

(About a 15-minute read. The Channels Project is a migration and updated post - it was first shared at the FUNdoing.com Blog. We are moving theoretical posts to OnTeamBuidling in an effort to organize content.)

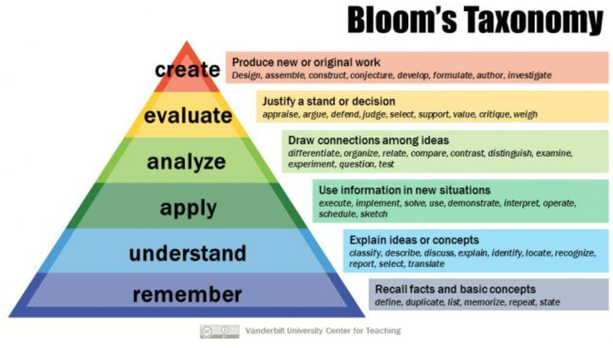

NOTE from Chris: This is an example of some 'Deep Work' programming - not meant to be quick and easy. The Channels Project combines team building behaviors and learning to understand the New Bloom's Taxonomy and how it can influence mindful experiences.

Those of you familiar with the original Bloom's Taxonomy know that it is a "classification of learning objectives" divided between the Cognitive, Affective, and Psychomotor learning domains. The intended goal of the Taxonomy, "is to motivate educators to focus on all three domains [and the different "levels" or "ways" of thinking], creating a more holistic form of education."

Using this New Taxonomy as a teacher (over the last 20 years), helped me focus on designing test questions that touched on the all the "orders" of thinking - including some basic "fact-based" questions like defining terms (lower-order thinking), up to "creating" something like a skills-based drill to practice throwing a ball (higher-order thinking). What I like the most about this revision to Bloom's is the inclusion of the "creating" process - something we like to do in adventure education. Creating is at the higher order thinking skill level in this new model and as an evaluation focus helps me to see what a student can put into practice. (Here is an 8-minute read for more, from Dr. Robert Talbert: Re-Thinking Bloom's Taxonomy for Flipped Learning Design.) A similar article (no longer available), back in 2012, inspired the Channels Project. Shortly after this 2012 read I set out to create an activity that could move a group through the ways of thinking to help educator groups understand and remember the areas of the revised (or 'new') Bloom's. The interesting discovery was that the ways of thinking are also obvious question prompts for the reflective process throughout the activity and during the processing session after the activity. The final twist to exploring the New Bloom's here is the notion of 'flipping' the model. We don't always have to start with lower-order thinking experiences (e.g., easy team building activities) and move up to something more complex. It's completely doable to jump into the complex and then back-track down the orders to uncover the learnings. So, here we go! The Channels Project Needs & Numbers (for each group in play):

The Channels Project Directions

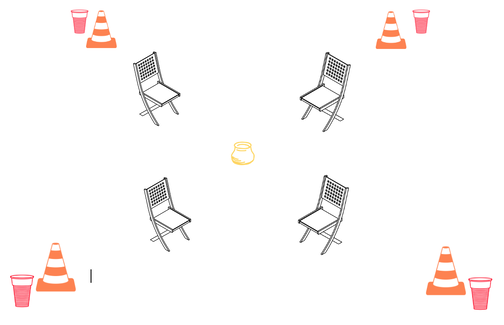

The Channels Project works well with 8 to 10 in a group. Multiple groups can work through it at the same time. (Maybe some collaborative interaction can happen?)

Time: This one has the potential to go for 30 to 90 minutes depending on the group(s) and the time you spend with discussions (and collaborations with multiple groups). Consider the possibility of spending two class sessions on this one if you are working in a school context. Set-Up: (For each group of 10 to 12 participants.) Mark the corners of a 25-foot sided square boundary area (can be indoors or outdoors) with the four cones. Place one chair inside the boundary area about 5 feet from each corner and an equal distance from each side. Place the wide-mouthed container directly in the center of the boundary area (wide-mouth up). Place one rollable object, that has been placed in a small cup (or bowl), at each of the corners of the boundary area - just outside the boundary area. Set down all the other supplies somewhere near the outside of the boundary area.

Objective: (Here is one possible script to introduce the activity):

The objective of The Channels Project is to create a transportation system of channels inside the boundary area designed to move all the 'vital resources' (small rollable objects in the cups) from their place of origin (the cups can be Factories ) to the central container (the Warehouse). Procedure: The expectation is to move all the vital resources available to you into the warehouse in 20 minutes. At some point during the movement of each vital resource, it must include the following action steps while inside the boundary area [read from 'The Channels Project Directions' handout you will be giving the group]: Each vital resource must 1) STAY OFF the ground (or Floor), 2) roll OVER something, 3) go UNDER something, 4) move AROUND something, 5) travel THROUGH something, 6) go BETWEEN two things, 7) travel HORIZONTALLY outside the channels, 8) drop DOWN through the air, and 9) move UPWARD. These actions do not need to go in the order listed on the directions I have for you; they simply need to be included with each vital resource. [Even though my groups have asked me to clarify some of these requirements, I've simply said, I will leave that up to you, as a group, to decide how you integrate these actions.] During the activity I will also ask you to adhere to the following Rules of Play: [Reading from the handout again, I share these Rules of Play before letting the group(s) start their work.]

Continue with the following information before the group is allowed to begin:

Please use the blank paper found in your supplies to diagram your plan of action. Included in The channels Project Directions, there is a graphic called, Bloom's Taxonomy. Reference this list attributes as you work through the planning of your transportation system. Here's the idea... After creating your transportation system plan evaluate and analyze how it works - you can practice your plan outside of the boundary area. Think about possible improvements to your system and apply changes if needed. After you reach your objective (or not, due to time limitations or loss of supplies), we'll take some time to talk about what you've come to understand and want to remember about your experience. If you were unable to meet the objective in 20-minutes, you can plan and implement another attempt today or the next time we meet. I'm now ready to answer any questions you have before starting the activity.

Reflection Questions:

As you can see, this experience will take time to work through. Use some of this time to check in with you group(s) and prompt some thinking and discussion about what's happening during the process , as well as the end. Here are some questions to consider:

I believe programming 'projects' like this can help our students (and other clients) dig into Deep Work. Life is not alway about 140 characters. Diving into a longterm endeavor builds tenacity and resilience. We can forge relationships because we get to know our group over time, through failures and success. We'll disagree but find common ground. We'll get to the end and determine what we did well and what we need to improve. Then, together, we'll take on the next project.

What other Deep Work can we program as team builders? We'd love to hear your ideas - leave us a Comment. All the best, Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

(About a 7-minute read)

Over my career as a team building facilitator, I have gravitated towards resources or tools that are made up of three parts. For example, the "What? So What? Now What?" processing model. The Traffic Light norming tool, "What do we want to stop doing (red)? What do we want to be cautious of (yellow)? And what do we want to go for (green)?" The typology of team interactions - Team Bonding, Team Building and Team Development. I've found threes are easy for me to remember and they are simple to introduce but hold a wonderful complexity when we dive in.

I recently found another threes tool, a little different than some of my others. It's not a three-parter, but a three-word phrase, "What's Important Now," or W.I.N. - The acronym is what I'm practicing to remember. I've put this W.I.N. in my toolbox as an in-the-moment assessment tool. Let me share a little information from the source to lead you into how I connected this tool to my work as a team builder. W.I.N. is from the book, Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less, by Greg McKeown (2014). The acronym is found in the section titled "Focus." McKeown credits, "What's important now?" to Larry Gelwix, a High School Football coach. Gelwix and McKeown share some insights about W.I.N. in relation to individual and team applications. As you read these insights, consider how they can relate to a team builder and even to the group a team builder is working with. (NOTE: If you find yourself 'reacting' to some of the words included in the insights, try to consider other ways the words can be interpreted.)

Below I share how I made the connections between the insights and team building. But before you read what I'm thinking, what are you thinking right now? If you're struggling with the semantics (e.g., game & playing), what else can the words mean? (Recently I heard Tim Farriss say, "We want to know what game we're playing, so we know how to play effectively and efficiently." If you're holding the word 'game' in your mind as a negative thing, consider a metaphor meaning.)

From my facilitator perspective, if I get too focused on something that didn't just work (first insight), I will miss the next opportunity to do a better job. "What's important now?" snaps me back to the moment - to "right now" (second insight) so I can "operate at my highest level of contribution" (third insight). By focusing in on the "here and now" my group and I can continue to make headway toward their desired outcomes - sticking to the strategies we're learning to meet the outcomes (third insight).

From a group's perspective, after I introduce the tool to them, they can also use the W.I.N. reminder. Individuals can self-reflect 'in-the-moment' to determine what's important at any given time (first insight).

Now, as team builders, we know that working out a problem that just took place might be the most important thing to do in that moment - using W.I.N. prompts the reflection to make the choice to stop or move on without dwelling on past behavior. For individuals, using W.I.N. can help remind them about how they are "playing" in the moment (second insight). Is what they're doing helpful to the group or not helpful? And what choices do they want to make moving forward. How can individuals unite in ways that contributes to the group's strategies for success? Finally, how does each person operate within their "highest level of contribution" (third insight) to the group? And how does the group find out about, encourage and support these contributions? W.I.N. is a new tool for me. I'm ready to experiment with what it can do. At times when his groups are 'stuck' unable (or unwilling) to move forward, my friend Tom Leahy likes to ask them, "Would you like a tool?" If they are interested, he provides them with one he believes could help them overcome their barrier. I've learned to use Tom's question with my own groups. Now I'm excited to share this one at the right time, with the right group.

All the best,

Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

P.S. Would you like a super-quick update when new OnTeamBuilding content is posted? Just fill out the form below and then click the big blue button. I'll keep you posted.

(About a 5-minute read.)

I first read about 'lagging indicators' from a new-year focused (2023) blog post from Ryan Holiday (author and Stoic thought leader - I created the activity, Obstacle Reflection using quotes from one of his books). A lagging indicator is an "output measurement" (according to a quick Google search). As Holiday puts it, "All success [or lack of it] is a lagging indicator." Lagging indicators give us vital data.

Specific to team building, what does success look like to you? What personal success do you consider? What contextual success do you measure? More often than not, I measure success in relation to the goals I set for myself. For example, one of my ongoing goals is to try a new activity (or a unique variation of an old favorite) during each program I facilitate. My lagging indicators (outcome measurements) show up in relation to how well I prepared for the new activity. I've found that the more time I spend thinking about and writing out the activity the better the outcomes - I've taken the time to prepare myself. I put in the work. In Holiday's post, he says: Nothing comes from nowhere. Not success. Not inspiration. Not the muses. Not writer's block. Everything is a lagging indicator of whether or not you did the work.

Using lagging indicators as data is important to our growth as team builders. It's why there is a lot of advice about taking time to reflect on your facilitation immediately after a program (intraspectively and/or with other facilitators). Here are a handful of after-program reflections:

After-program reflection does not need to take a lot of time (unless you want it to). Use indicators to identify what's working - recognize and repeat. (Don't forget to celebrate the goodness!) Then determine what didn't work well (maybe just one thing) and make a plan to change it for next time. In most cases, based on my experience, when I've planned well with purpose, programs go well. When I put in the work and create of program I believe will lead my groups' to their outcomes, I see more 'success.' (It's that old saying, "You get out of it what you put in.") Moving Forward What are some of the lagging indicators you want to work on? How are your processing skills? How are you feeling about 'opening' programs? How are you at wrapping up or 'closing' a program? Do you know enough activities to plan for a wide range of diverse groups (if you want to work with a wide range)? How are your online team building facilitation skills? How much work needs to go into meeting your goals? Can you (will you) put in the time? Lagging indicators will show you where to focus the work. All the best, Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

P.S. Would you like a super-quick update when new OnTeamBuilding content is posted? Just fill out the form below and then click the big blue button. I'll keep you posted.

(About a 5-minute read - and some thinking time. This is a migration and updated post - it was first shared at the FUNdoing.com Blog. We are moving theoretical posts to OnTeamBuidling in an effort to organize content.) Purpose Statement: The "Let's Think..." series is meant to be a reflective tool for team building educators. There are lots of 'right' answers to the questions or statements. Considerations are subjective and relative to each educators environment, program boundaries and their training. A 'hat-tip' goes out to Jim Grout and the High 5 Adventure Learning Center - their "Caught you Thinking" process always keeps me thinking! I have an open document on my computer and one on my phone called "Running Notes" - these documents contain random thoughts I have about anything from team building activities to recipe ideas. Recently, I was reviewing these notes and had a few entries I marked as, "thoughts to work through." I thought it might be interesting to see what your thoughts are on these thoughts:

This FUNdoing Post (that is updated here), also included one Comment from a fellow team builder, P.B. - I didn't want to leave them behind. Again, one person's perspectives. There are many more from many others. WHERE TO STAND - I normally have groups stand in a circle with me being a part of that circle, so that they can see and hear me and i can see and hear them. I like to have groups name/categorize the circle and have poses to go with them (superhero circle, airplane circle etc), so that i can shout out the name of the circle and have them form it and know i have immediate attention. Adults posing as airplanes is particularly funny to me. WHAT MIGHT WE LOOK LIKE - I wear a staff uniform as required but will tend to wear something silly and colorful alongside it but hesitate to address it to allow humor to initially break the ice with a group. But it does depend on the group. Some groups expect professionalism (although in my mind i have fun and play for a profession). HOW LONG TO PLAY - I try to nip the activities in the bud at the peak of them or just past it, just before disinterest sets in. Im an advocate of a CHALLENGE course and not a SUCCESS course. If a group does not succeed then that leads onto some excellent processing. But ending an activity is a judgement call, some groups want to persevere and get more out of completing an activity and some lose interest and morale. This is definitely an area of discussion that i have thought about a lot and would love extra input on. What are your thoughts about these questions? What else can we 'think' about? Leave us a Comment so we can learn and grow together.

All the best, Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

(This is a migration and updated post - it was first shared at the FUNdoing.com Blog. We are moving theoretical posts to OnTeamBuidling in an effort to organize content.)

This post was inspired by Katie, a team builder, adventure educator and FUN Follower. Her situation is a common tale - she wanted something different. (An aside - I'd love to study what motivates team builders to want something different. I know some that don't - and it works for them.)

In an email Katie told me: My favorite name game is Group Juggle because it seems to be the most helpful in actually learning names. But, after you facilitate it for the hundredth time it's time for something different. Then she asked, Do you know of any [other name games] that are as helpful and active as Group Juggle that work with youth and adults? In my response to Katie (along with some suggested Name Games), I said that I know "Name Games" in two ways:

I also told Katie that if the facilitator actually takes the time after an activity (like Group Juggle) to go around and ask for volunteers to call out as many names as they can, then we're practicing and learning names (and offering a "challenge" as well - Who will take the risk at making a mistake?). A win-win learning opp in my book. (But, in my experience, I don't see this happening very much by team builders who use name games - it might not be necessary, or it simply might not seem important enough. Learning names important enough - don't get me started.) If I'm playing a 'name game' with my group, it is always for the facilitated objective of learning and practicing names. The goal is to learn names, any other outcome is secondary (and certainly a good way to get some 'mileage' out of an experience). Below is my all-time favorite way to use a Name Game for learning and practicing names in a fun and purposefully stressful (educationally speaking) way.

Toss-a-Name Game & Testing Out Toss-a-Name Game comes from the first edition of Silver Bullets (Rohnke, 1984). For a circle of about 24 participants, you need a bunch a safe tossable objects (safe enough to hit the cranial regions without damage - not that we're doing this on purpose, but there is a possibility of cranial contact!). I show up with at least one tossable for every two people.

One object starts the action. The person tossing the object (anyone can be chosen to start the first object) is asked to:

The next person to possess this first object (since the intended person might not get the toss), follows the same PTP - name, connection, THEN toss. This one object goes around the group, without stopping, in any which-way - no 'pattern' is required (like in Group Juggle). Once the PTP process is understood, after a minute or so, I will then stop the action and tell my group about Testing Out. Here's a possible script: Now that you understand how PTP works, I would like to give you a challenge - remember, it's your challenge, it's your choice, so it's up to you if you want to try "testing out." We're going to continue the activity, following PTP. After a few minutes I will stop the process and ask who would like to test out on Names. If you are up for the challenge, the first thing you will need to tell me is what grade you want to go for - this means, getting 90% or more names correct gives you an "A" grade. (For an A+ you need to get all the names correct.) A "B" is in the 80th percents, a "C" is in the 70th percents, and so on. If you don't get the grade you want, you can try again after another round of tossing play. "Testing out" on names has proven to be a successful challenge for my groups. Even though there is no real grade given (nothing is written down), going for the "grade" seems to influence the learning process and (self-) motivates (most) participants to practicing names as they toss objects around the group (and noticing other names when they are not tossing). If a person doesn't know someone's name they can ask for help, "Hey, you in the red shirt, please help me out. What is your name?" Once a name is given, then it's practice time - name, connection, THEN toss. Increasing the Challenge Level Now, something else starts happening in Toss-a-Name Game. While PTP is going on, more objects are added to the process when the facilitator feels the group can handle more - I add one new object every minute of so. All the tossing about creates some distractions, anxiety and fun (now you get the cranial reference) while the potential learning is going on. Okay (don't forget), after every couple of minutes, stop the action and ask if anyone wants to test out. In the beginning, I might simply ask, Who thinks they have 50% of the names? Maybe 70%? How about 80%? (You get to see if there is some learning going on and if someone may have the confidence to try and test out - those 90 percenters.) Okay, who's willing to try the test? I'll take two or three volunteers. I ask for the grade they want then let them have at it. We all celebrate every person's attempt, whether it was a success in their eyes or not - because they can try again another time. One of the secondary facilitated objectives of this activity experience is to show the group how you are all creating a safe learning environment - if you take a "risk" we will support you. With that said, I am always one of the first to "test," and I usually have to try a few times before I get my A+. (I show my group I'm willing to take the risk as well - and willing to "fail" and learn from the process.) Now, you might be thinking, Testing is the outcome Chris! I thought you said learning names was the outcome? Again, I see testing as the motivator - something of choice is on the line. Each person chooses her/his own grade (goal) if s/he even wants to test out, does their best and celebrates the attempt knowing they gave it a shot (took a risk in a safe environment). This is setting the stage for (leading into) the kinds of activities and experiences coming up in the program. There will be some risk involved, but if the group can practice supporting each other during their risk-taking, they will find success - in the many ways they define it. All this, you can do with a Name Game. Katie, thanks for letting me share your question. If any of you out there want to share your favorite Name Game, leave us (Katie and me) a comment below. Thanks! Have FUN out there! Chris Cavert, Ed.D. P.S. For me, my most practiced way of learning my students/participants names is to have them create Name Cards (like the ones we use for, Name Card Return that uses names). I'm practicing during the activity, then after I continue to shuffle through the Name Cards as they are working in order to practice and remember. I can usually know, and remember everyone's name (I'm good with this process up to about 30 people) within an hour.

Would you like a (super) quick email notification when new OTB content (blog post or podcast episode) is available? Fill out the form below and we'll let you know.

I want to share this information (resource) in order to support some of the work you do as a team builder. It would be a pretty good bet that this will not be new to you. Use it as a useful reminder and reference - a guiding star maybe, if the light works to inspire.

In 1998, a United Nations Inter-Agency Meeting was held at the World Heath Organization's Headquarters. The aim of the meeting "was to generate consensus among United Nations agencies as to the broad definition and objectives of life skills education and strategies for its implementation..." As promoted by WHO, "Life skills education is aimed at facilitating the development of psychosocial skills that are required to deal with [manage] the demands and challenges of everyday life." (Reference: "Partners in Life Skills Education" document, 1999. NOTE: This document is a seminal work focused on the importance of the specific skills [concepts] listed below. Other 'kinds' of life skills education have been added - see the WHO.Int website for more.)

My take on this information, based on searching "Life Skills" at various site, is that these skills are just as relevant, if not more so today, than they were when documented over 20 years ago (and even before 1999). As team builders, we can continue to practice and build these skills and use the WHO reference, "according to the World Health Organization," if some validation is needed to make your point. (I hope, at this point, these needed skills are pretty common knowledge!)

To enhance your 'purposeful programming,' the idea is to connect these skills into the activities you are using in order to practice the skills. Use the language to help your participants 'name' what they are practicing. When we can name something it is often easier to identify what we are doing, what we can be doing and how we can talk about it with others. Then, we can get better at using the skills. Life Skills [Concepts] we can work on together during team building:

Going Deeper

If you want to become REALLY GOOD AT helping groups practicing these Life Skills, get more specific. I interpret the items on the list above as 'concepts' - a "general idea derived from specifics." The specifics being 'skills' - things you can see and hear (in other words, behaviors). This overall point of view is rooted in Behaviorism. I have learned that Behaviorism is 'a' way to educate, not the only way. It is a tool to use in the appropriate circumstance, not the only tool in the tool box. The Homework: Do some research on each of the concepts listed above to answer the following question: If you were to see a group working through the process of critical thinking (for example), what would they be saying and doing? Your answers are the skills, or behaviors, related to critical thinking - this is the 'skills list' for that concept. Then, when a group asks you to help them practice critical thinking, you program activities you know will involve critical thinking skills - the skills you can see and hear. Then, the group (and you) can evaluate if and when the skills are being used, how well they are working and what skills need more practice. What I've shared above is a (super) simple snap shot of, 'Purposeful Program Design' - something I've been teaching and training for the past 10 years. When we can learn to identify the skills sets (behaviors) of the concepts we aim to practice during team building (e.g., Leadership is another concept), we can (laser) focus in on the best activities to practice the skills. And, better meet the needs of our participants/groups.

Dive in. Build your skills lists and facilitate programs that will truly help groups learn and grow. Life skills education is a major focus of what we do. I challenge you to do the good work. And do it to the best of your ability!! (And, I thank you for it.)

Keep me posted. Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

Would you like a (super) quick email notification when new OTB content (blog post or podcast episode) is available? Fill out the form below and we'll let you know.

This is a conversation (video recorded with ZOOM) on Ground Rules and Group Contracts (e.g., Full Value Contract) between John Losey and me (Chris Cavert) recorded on Sept. 19th, 2019 (about 54 minutes). I wanted to get this into the OTB resources so it's easily searchable and accessible.

Below you can read some of the thoughts from the conversation. We would love to hear your thoughts on the topic. Please leave us a Comment.

What are ground rules or contracts? These are agreements on, "how we are going to BE together." In other words, what are the "rules" we're going to follow when we're together?

Many people (e.g., Corporate Adults) come into programs with expectations. Ground Rules and Contracts help us "align" expectations around how they treat each other and how they want to be treated so there is less misunderstanding. "What makes it fun for you when you're with a group of people?" This might be a way to approach rules or contract development. (Start from what your group may understand - fun, we hope, is understandable to most people.) Working with adults, John shares, "I want to have them take control over how they want to treat each other..." "If this is going to be the 'perfect' meeting, what's going to happen. What do you [the individuals] need from it, what does the group need from it?" (John leads with this idea through, "Setting goals and ground rules.") "What do we need from each other to best reach these goals?" With adult learners (research says), if the facilitator (leader) takes too much control, it limits the buy-in from participants. (How does this play out based on the time you have with a group?) When people feel like they've been heard, they're more likely to respond and interact in positive ways. Including 'people' in rules/contract development, whether group led or facilitator led, increases the likelihood of positive interactions. (A line of thinking: If this, then that...) You [the educator/facilitator as a 'role'] shouldn't totally eliminate yourself from the process, but it's good to be aware of your positional power, even your authoritarian or experiential power...and not abuse that and steal from the groups learning. Ground rules and contracts are not just about team building and group process, they are functional tools to get you where you want to go more effectively and efficiently.

We would love to hear your thoughts about Ground Rules and Contracts. Leave us a Comment.

Be well!! Chris & John

Would you like a (super) quick email notification when new OTB content (blog post or podcast episode) is available? Fill out the form below and we'll let you know.

|

OnTeamBuilding is a forum for like-minded people to share ideas and experiences related to team building. FREE Team Building

Activity Resources OTB FacilitatorDr. Chris Cavert is an educator, author and trainer. His passion is helping team builders learn and grow. Archives

January 2024

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed