|

The following was part of a recent email I received:

When you are writing up your activities [for the FUNdoing.com/blog], I would find it really helpful to have an added header that includes the activity's goals and/or objectives at the top of the description. Even though I was familiar with a number of the activities you described in the recent [FUNdoing] Friday emails [June 12th, the Group Juggle Variations & June 24th, the Mr. & Mrs. Wright Collection], I re-read the descriptions several times because the activities had twists and therefore I wasn't sure whether the typical goals/objectives had shifted. In gratitude, Pamela

This email inspired me to share my perspective about, what Pamela phrases, "the activity's goals and/or objectives..." (Thanks Pamela for the request and inspiration.)

The short version: It is very common for goals and objectives to be considered synonymous - this can happen when a goal is woven into an objective (totally fine when done with purpose, in my opinion). For clarity, I separate the two when training educators (e.g., team builders). In most cases, objectives originate from the educator (i.e., team builder, programmer, teacher, curriculum developer). Goals are created by participants - especially, during teambuilding programs for practicing the behaviors related to goal setting. If you are happy with, and already feel comfortable with these distinctions, you might not need to dive into the long version below. I have found (over the past 20 years), that clearing up grey areas for learners (e.g., synonymous terms), practice seems to be clearer. (How about this one: What's the distinction between processing, debriefing, reviewing, reflection? How do you explain this to new learners?)

Here's a long version - the way I teach the concepts of objectives and goals. My 'goal' here is to share my thinking in under 500 words in order for you to get the idea (expanding on the idea can be for another day).

Objectives In the context of teambuilding programs, there are two kinds of objectives:

Activity Objectives Literally, what is expected based on the activity description. For example: Hand off what's in your hand to the person on your right or left based on the language in the story. (Activity: Mr. & Mrs. Wright). Isn't this a goal Chris? Good question. After reading the 'Goals' section below you will see the distinction. Another quick example. Toss this object around the group as quickly as possible following these rules..... (Activity: Basic Group Juggle - video of the basics) Everyone participating in the activity is made aware of the objective through the directions (well, they are told, but awareness might be limited). Facilitated Objectives I describe these as possible learnings. When a client asks me to 'work on' certain concepts with a group or help them learn something (e.g., communication, trust, leadership, problem-solving, relationship-building, helping, having fun), I consider and program activities that, I believe, will help the group practice the concepts. (My considerations are based on my experiences with the activities I know.) My plan is to 'facilitate' towards the clients desired objectives - facilitated objectives. Participants in the program may or may not be fully aware of all the facilitated objectives I have planned. This depends on the context of the group. For example, based on program/learning objectives, it might be an advantage to share facilitated objectives with an adult group, but with a youth group it might not be necessary. Goals Goal-setting is the common term for an expectation one wants to meet (personally or as a group). We don't hear (or use) the term objective-setting. So, I like to purposefully separate the concept of goals from objectives. As noted in the context of team building, an objective is presented by the educator, goals are developed and pursued by the participant(s). In the most straight-forward way I can share this, there are two types of goals we tend to use during teambuilding. Product-oriented goals and process-oriented goals. A product-oriented goal is, most often, a result of work completed - often a number or time. A process-oriented goal is usually something someone or the group agrees to do during the work that leads to completing a task. In theMr. & Mrs. Write activity, a product-oriented goal might be for participant to have only one object in his/her hand at the end of the story. A process-oriented goal might be for everyone to have permission to call, "Stop" if there is a problem during the activity or if someone needs some help on their way to meeting the product-oriented goal. In the Basic Group Juggle activity, a product-oriented goal can be a certain time to achieve. The process-oriented goal might be to call out names before tossing an object in order to increase the level of catching success. In the midst of problem-solving towards the objective, the group develops goals to strive for - hence, practicing goal-setting behaviors in order to meet objectives.

Professional Development Opportunity

If you're up for a little professional development challenge, dive into the Mr. & Mrs. Wright Collection & Group Juggle Variations FUNdoing Blog posts and write up the Activity Objectives, Facilitated Objectives and a Goal for each one of the activities. If you would like, send them to me and I'll provide you with some feedback. I hope you found these distinctions useful. We'd love to hear your thinking on the subject. Leave us a Comment below. All the best, Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

Would you like a (super) quick email notification when new OTB content (blog post or podcast episode) is available? Fill out the form below and we'll let you know.

0 Comments

(This is a migration and updated post - it was first shared at the FUNdoing.com Blog. We are moving theoretical posts to OnTeamBuidling in an effort to organize content.)

An Alfie Kohn* blog post, Transformation by Degrees inspired me, a while back, to put together a few thoughts I'd been having about 'participant-centered' team building. Now, as team builders and experiential educators, most of us know how important it is to build a trusting community of learners by first getting to know our learners (as the teacher discovered in Mr. Kohn's first story). After we get started, how do we, as team builders, shift more (or all?) "control" of our learners' experience to them?

*Alfie Kohn is an educational thought leader advocating for less homework, less testing, and more "student-centered" educational practice. He is one of my heroes.

At this time, I have more questions than answers about how to make team building more "participant-centered." In this post my intention is to light the fire. Let's see what we can come up with together. To get the wheels turning, let me share a couple of recent stories and then share some thoughts from Kohn's post, Transformation by Degrees.

A recent change to my facilitation process has been to let go of the traditional "harness & helmet demo" and have my groups figure out how to get their PPE on appropriately. As a whole, the group is in charge of getting this task done correctly, meeting safety standards for proper harness and helmet fit. Now, I do give them some safety standards information: The waist belt must be above the waist. There should not be any twists in the webbing of the harness. And, the helmet must not expose the forehead or fall down over the eyes when climbing. (I am also wearing my PPE appropriately - meeting safety standards - as an example.) This participant-centered approach has become a nice addition to a group's "team" building experience. In most cases so far, it also helps when there is at least one person in the group that has climbed before (having worn a harness). My groups have ranged from 5th graders to adults. Yes, there does need to be fixes from time-to-time (that I point out), but the group is in charge. (NOTE: No one climbs without my approval/visual check - so, if I would say, "You're not ready yet," the participants helped each other reach passing criteria.) On another note, here is a recent story from a fellow facilitator that highlights a factor of "control" (or management) of time with a group. Working with a new group of 12 participants (for a half-day program), my friend wanted to go around the room for (what she requested) "quick" introductions. The first few people shared their name, their role at the company and a little bit about themselves (one-minute tops for each) - all was going as planned. Then, the trend changed. The stories from each participant got longer. The planned (on paper) 10-minute introduction activity turned into over 25 minutes of sharing. So, how do we adjust "control" and still get in everything we've planned? (The thinking: "If we let them be in charge, how will we get things done?") Do we impose a time limit on things so we can get to other tasks on the list? Are our programs about quantity or quality? Can there be both? How much planning with participants can take place before a program? Do we (and they) have time to do this? Again, more questions than answers right now, for me.

Here are some thoughts from Mr. Kohn (from Transformation by Degrees) about moving/ sharing control:

"...those of us who are trying to serve as change agents in education had better not count on teachers’ [team builders] waking up one morning prepared to adopt radically different practices. In fact, we would do well to have some examples ready for how they can get from here to there step by step." [Training team builders to be more participant-centered will take some time and role modeling.] "It is possible to edge slowly away from traditionalism with respect to just about any specific practice." [Try one participant-centered strategy at a time and maybe for just part of the program.] "To learn something about the students [participants] was to transcend (or at least create the conditions for transcending) traditional pedagogy [team builders are pretty good at this part]. To invite the students to talk with, and then introduce, one another was to transcend an ideology of individualism — learning as an activity for a roomful of separate selves. To ask (rather than dictate) what the interview questions should be was to transcend the default model of top-down teacher control. In each case, what was challenged had simply been taken for granted." "At each stage, one can move ahead only after confronting the unsettling truth that what looked like a destination turned out to be just a rest stop. There’s farther to go on this journey." [Find out from the group what else is important to do once you believe you have reached a destination with your group - you might think they are done, but do they think so?] “My job,” a teacher in Ohio once commented, “is to be as democratic as I can stand.” Had she invited me to append a friendly amendment to her declaration, it might have been, “… and my other job is to push myself to be able to stand more democracy next year than I could this year.” "Perhaps our motto should be: Change by degrees - but don't underdo it." Kohn

What are some of the changes you are making (or have made) to be more participant-centered in your programs? What are you doing as a team builder, that could be done by the group? We could put a participant-centered 'in-practice' document together and share it with the world. What do you say? Add your ideas in the Comments below.

Keep us posted! Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

Would you like a (super) quick email notification when new OTB content (blog post or podcast episode) is available? Fill out the form below and we'll let you know.

(This guest post is from Jim Hooper. Jim shares with us his use of the term 'Bridging' in order to better visualize the connecting between team building activities and real life. Thanks Jim!!)

As a Naturalist for the YMCA Greenkill Outdoor and Environment Education Center [one of the oldest Environmental Centers on the Northeast - and, it's not a typo], I began facilitating ropes course programs a little over 20 years ago. In subsequent years, I have moved into Summer Camp administration, serving as the Camp Manger at 4-H Camp Bristol Hills since 2005. One of the aspects of this position is the facilitation of groups on our ropes courses, and perhaps even more importantly, the training of 15-20 seasonal camp staff each summer as we prepare for some 300 youth to participate in ropes course programming.

"We are very deliberate in working with group leaders to understand what the group is hoping to accomplish from their time with us..."

With the growing popularity of recreation-based adventure programs, aerial parks and so on, I’ve had the opportunity to talk with school teachers, coaches, and other group leaders about what sets our program apart from those purely recreational programs (the local ski resort recently built a large aerial park a few miles from our camp, and have been pumping a lot of money into marketing those recreational opportunities). And while there are many differences between our program and theirs, one of the principle differences is our focus on group development as well as individual challenge. We are very deliberate in working with group leaders to understand what the group is hoping to accomplish from their time with us, and then we select challenges that we believe will shed light on those issues. We put a heavy emphasis on how the experience at camp, and on our ropes courses, relate back to the real lives of our participants. This is in line with the “What, So what, and Now what?” approach to adventure education. Sure, we had a great time swinging across an imaginary lava pit and landing in tiny hula hoops, but realistically, how does that help us when we go back to school, the office, the field, etc. It’s not like we will ever need to swing from cubicle to cubicle on a rope!!

"I truly believe that effective processing can come at any time throughout the experience, before, during and after."

Typically, skilled facilitators will employ reflective techniques throughout a program to help participants see the correlations between the program and the tasks that a group is expected to perform when they go back to the “real world." I often find that young seasonal staff, ranging from 17-21 years of age, are frequently intimidated by this phase of the program, and will shorten the processing phase in favor of cramming one more activity in before lunch. This is an area that I have tried to focus on during our staff trainings, and I have found it really helpful to talk about this process not as “processing” or “debriefing” or even “reflection”, but as “bridging”. Personally, I find that the former choices often lead to groans, moans, or general “oh man, here we go again” response. Additionally, I have found that these terms imply that processing is something that only happens after an experience comes to a close, and I truly believe that effective processing can come at any time throughout the experience, before, during and after.

"There is a very visual element to the term bridging, and particularly with the young staff that I work with, the visual aspect appeals to the concrete thinking perspective."

I far as I can remember, I first ran into the term of “bridging” in “Processing the Experience: Strategies to Enhance and Generalize Learning” (2nd. ed.) by John Luckner and Reldan S. Nadler (though I don’t have a copy of it anymore to verify that). I really connect with the term on a few different levels. First, I believe that staff see the activities we facilitate in our programs as one world, separate from real life, and that the processing phase is the way that we connect, or bridge, those two worlds. There is a very visual element to the term bridging, and particularly with the young staff that I work with, the visual aspect appeals to the concrete thinking perspective. Additionally, I find that bridging lends to a more proactive approach to the process. Just like when we are going to build a bridge, we need to prepare and gather resources before we begin building. We also need to be able to interrupt construction if we see something that demands immediate intervention. And of course, once the bridge is built, we need to travel across the bridge, carrying the experiences from one world to the other. I have found that staff are able to relate well to this approach. It gives them the confidence to think about processing in a broader perspective, rather than just “something we have to do at the end of every activity." We also spend a significant time during our training, talking about processing fatigue; the idea that not every single activity needs to be processed, and that it’s imperative to vary your bridging techniques so that participants don’t begin to dread the time immediately following an activity.

We would love to know about your thoughts on Bridging. Leave a Comment below.

All the best, Jim & Chris

Would you like a (super) quick email notification when new OTB content (blog post or podcast episode) is available? Fill out the form below and we'll let you know.

(This is a migration and updated post - it was first shared at the FUNdoing.com Blog. We are moving theoretical posts to OnTeamBuidling in an effort to organize content.)

This drop-in training technique allows for some relevant observation time...giving 'bits' of information instead of overload.

Pedagogy, in it's simplest form, is an educators collection of "activities used for educating or instructing that impart knowledge or skill" - it is what educators DO to transmit information to students. And, as far as I know, no one has found the "best" pedagogy for educating. One could argue that there are as many pedagogies (ways of imparting knowledge) as there are educators.

As I have written about in the past, adventure practitioners are educators (Team Builders as Educators: The 3 Roles), and they too have pedagogies - ways of working with their groups that impart knowledge or skill. What follows is a look at another educator in the adventure educations field, the Trainer. Whether you are an 'in-house' trainer working with your own team building staff who lead programs for your clients or you are a 'lead' trainer (e.g., Training Manager) for a training company that trains trainers who train other adventure practitioners (the training companies clients), here is a training technique you can use to help educators learn and grow. Training Educators What "activities" (defined in a number of ways) do you use to impart knowledge and skills to your staff or trainers so that they are able to find success as an educator? With the limited amount of time you have to make an impact on them, what will be the most effective and efficient way to use your pedagogy? I while back, I ran across a useful blog post from from Faculty Focus entitled "Using Guerrilla Tactics to Improve Teaching." The ideas from the authors of the post are relevant to any educator who is tasked with training other educators (please read the article for the finer details of the process). I've taken some editorial liberties to make the "ground rules for guerrilla teaching" fit into an adventure education model I will call "Guerrilla Training:"

As the Guerrilla Tactics blog authors note, "In the spirit of guerrilla marketing [a creative low-cost strategy to meet conventional goals] there are several educational "buzz" benefits created with minimal direct cost" - role modeling, collaboration, flexible training times, sharing expertise, "bits" of information instead of overload, and showing support for the trainee. This "drop-in" training allows for some relevant observation time for the trainee. Something that is difficult to building into training sessions but very important to include. Making Guerrilla Training part of your training pedagogy might prove to be useful, effective, and efficient. Let me know how it goes. And, if you have other pedagogical training ideas for us please share in the Comments below. All the best, Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

Would you like a (super) quick email notification when new OTB content (blog post or podcast episode) is available? Fill out the form below and we'll let you know.

Since moving to Colorado three years ago, I have met a lot of amazing facilitators in the area. Leo Shettler is such a person. After I saw him open with his frame, 'The Basic Skills for Being Human' I knew you would want to learn about it. Leo has kindly obliged. Thanks Leo, may this one live on forever. (So, amazing!)

"Imagine a school where everyone is kind and helpful and considerate to everyone there, teachers and students alike. Imagine walking down the hallways between classes and nearly everyone is smiling." from Leo

FRAMING 'The Basic Skills for Being Human'

Imagine a school where everyone is kind and helpful and considerate to everyone there, Teachers and students alike. Imagine walking down the hallways between classes and nearly everyone is smiling. No one is being pushed or shoved or bullied or yelled at or made fun of. Imagine that between every class at least a dozen other kids give you, and everyone else, a smile or a high five or a friendly greeting as they pass you by on the way to class. Imagine sitting in a classroom where no one is afraid to raise their hand to say they don’t understand something or to ask a question of the teacher. Imagine a school where the kid who used to always eat lunch alone in the cafeteria is now joined nearly every day by a compassionate student or two wanting everyone to feel they belong. Imagine a school where everyone wants to help everyone else succeed and be happy. Now imagine a workplace with the same kind of people, imagine a town, a whole world. How can we as individuals get on the right path to create this kind of school, workplace, country or world? What skills are needed? The activities and adventures you will be invited to participate in today are designed to help us all create such a school, such a workplace and such a world.

"But, before we get started on these adventures, I have three questions for you."

Question #1. Are some basketball players better at playing basketball than others? If so, how can you determine this?” (Students will respond by pointing out the sub skills of basketball. For example, shooting, passing, guarding, etc) Question #2. Are some bears better at being bears than other bears? (There will be a mixed reaction with participants taking opposite sides of this question. After some discussion about the sub skills of being a bear, such as finding food, climbing trees, mating, raising cubs, etc., there will be general consensus that some bears are better at being bears than other bears. The point of the discussion is to create an awareness that animals, including people, have sub skills that come with their nature and the better they are at performing those sub skills, the “better” they are as a creature. Question #3. Are some human beings better at being human beings than other human beings? (You will generally get blank stares of disbelief at this question. I remind them that I did not say “of more value than others” and that by observing the sub skills of basketball players and bears they were able to determine an answer to the first two questions.) So then, what are the most basic and fundamental skills needed in order to be a good human being? After participants list their opinions, I distribute a one page handout (PDF download below) listing, in alphabetical order, 14 basic sub skills of being human. One sentence at the top of the page states that the frequent practice of these sub skills will result in you becoming a better human being. The sub skills (sometimes called virtues) are listed with their definitions. Participants are asked to take turns reading these sub skills out loud. Finally, before starting the first activity, participants are asked to watch for good demonstrations of these sub skills from one another throughout the team building/challenge course activities and be ready to acknowledge others for demonstrating the sub skills. (Leo's shares, "Through my observations, acknowledging a person for any behavior tends to reinforce that behavior and increase one’s desire to become even more skilled at it." Practicing these sub skills can help us be more 'human'.)

The Basics Skills for Being Human, Handout

Thanks again to Leo for helping us learn and grow. Let us know how this works for you.

All the best to you! Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

Would you like a (super) quick email notification when new OTB content (blog post or podcast episode) is available? Fill out the form below and we'll let you know.

(This is a 'migration' and updated post - it was first shared at the FUNdoing.com Blog. We are moving theory posts from FUNdoing to OnTeamBuilding as a way to organize content.)

"Over time, your character, competence and caring may be revealed by your actions. In a micro world, it is the right words used at the right moments that spark conversations and build bridges between people" Jeff Schmitt

The main purpose of adventure 'education' is to explore, learn and grow in the areas of personal and interpersonal relationships. Some recognize this as the development of pro-social skills and social emotional learning. Some years back now, I ran across a leadership article at Forbes Online from Jeff Schmitt. I thought it might be a good for educators (i.e., team builders) as well - at least it's a good reminder of the simple things we can do (model) to encourage pro-social development.

Adding to Schmitt's encouragement about using the phrases, it's also a nice idea to pass on (teach) this information to our participants when appropriate (e.g., a classroom teacher modeling, showing and practicing the phrases during processing sessions). Schmitt shares 15 Phrases That Build Bridges Between People. Teaching and encouraging these phrases does not take a lot of time, only commitment. Hopefully we are already using them to strengthen the communities we belong to and the groups we work with. Below is a quick reference to the phrases in the Forbes article. I've also included some additional phrases from my friend Phil Brown who shared them in a Comment at the original Building Bridges post. From Schmitt:

Here are the additional phrases from Phil:

Phil also share some thinking around his approach to building bridges: In addition to the phrases I use, I find that the tone of voice is incredibly important in making my participants feel comfortable. Being from England my accent helps a lot too, but I truly feel that (and I train my staff that) a calm tone is essential in making participants feel comfortable and looked after. Jeff, Phil and I ask, "What phrases do you use to make people feel more comfortable, motivated, and appreciated?" Share your thoughts in the Comments area below. BONUS TOOL (Print-N-Play) Here (below) is a print-n-play tool (set of cards) you can use as a visual reminder of the phrases. During a processing session you can scatter out the cards within the center of your processing circle. Participants can scan the cards and use/practice (if they choose) any of the phrases when address others during the discussion. Again, this is simply a tool you can teach and use in order to practice pro-social behaviors within the appropriate context.

All the best,

Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

Would you like a (super) quick email notification when new OTB content (blog post or podcast episode) is available? Fill out the form below and we'll let you know.

"We want to educate students so that they become larger, more open, more independent human beings, able to function effectively in a world of rapid social and moral change. We believe that a person struggles toward these goals through a process of integrating his thoughts, his concerns and his actions. Our teaching will be directed toward the development of this perspective, this sense of an integrating self." (Borton, Reach, Touch and Teach, p. 66, 1970)

This was the spirit of a group of teachers in the mid-1960s - the spirit, or soil, in which the seed of the 'What Model' was planted and grew.

"We wanted to build a curriculum which would explore the concern for identity by concentrating on the students' own sense of disparity between what they thought about in school, what they were concerned about in their own lives, and the way they acted" (p. 66). In essence, the What? So what? Now what? model was created as a 'process' to help young people navigate every day concerns. The 'Curriculum of Concerns' these teachers built was the overall structure, the What Model was one of the tools within the structure. Terry Borton is the author of, Reach, Touch and Teach: Student Concerns and Process Education, published in 1970. Borton, at the time, was an English teacher in the Philadelphia schools during the desegregation era in the United States. After his first year of teaching English (1964), he was inspired to, "talk over an extended period of time with students about things they thought were important" (p. 23). The following summer (1965), Borton and a handful of teachers, "got the chance to run an experimental summer school [Friends' Summer Workshop]...to make an unfettered attempt at finding out how to meet students where they were and show them where they could go" (p. 23). The curriculum they envisioned was designed to explore the diverse social aspect of human life and self-identity. The same area of focus we still have today as 'social' educators and team builders. I could go on with rich examples from the book about these incredible teachers and how they learned to meet their students where they were, a well-known group facilitation strategy still important today, but I'll leave that up to you if you're interested in getting the book. Let's jump to how the What Model came to be. Through a variety of classroom activities like role plays, art and poetry, the students in the Summer Workshops were taught useful things about personal development and human relationships. They were also taught about the many ways of responding to different situations that were common in their lives (again, practicing in the classroom). But, the teachers thought, "unless our curriculum explicitly made the transition from literary metaphor to process, we [doubted] many students would make it [out in the world] by themselves" (p. 75).

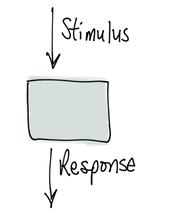

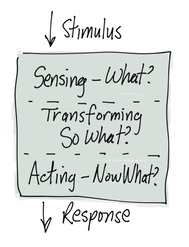

According to behaviorist theory, "[c]hanges in behavior are seen as a function of the stimulus and the way the response is reinforced. Reinforcement of a particular response is usually accomplished by rewarding its occurrence" (p. 77). In behaviorist practice, this process, more often than not, required at least two participants. Someone would be providing the stimulus and another person the response (e.g., teacher and student). Then, if a different response was desired the stimulus provider would make a change in the stimulus in the hopes of a different response.

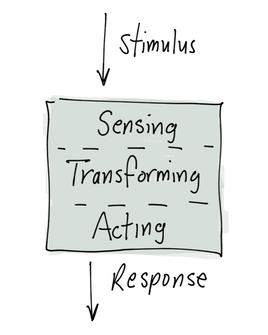

The teachers surmised, the process (or tool) they would teach to their students would initially involve sensing information or stimuli - noticing something important to them. Then, transforming this information by giving it personal meaning and value. Finally, acting on this meaning and value after, "rehearsing possible actions and picking one to put into the world as an overt response" (p. 78). "The person using these processes," the teachers believed, will not be "governed solely by the nature of the stimulus and/or reinforcement of the response but is also influenced by feedback on how successful [s]he is achieving [her]his own goals" (p. 79).

Here is the crux of this historical exploration. The What Model was initially developed as a personal growth tool (process). Something young people (the teachers' students) could apply out in the world to help them in the pursuit of their goals - to help them act upon their real life concerns. Within this Model, awareness and feedback were vital. Borton writes, "awareness of the difference between his [sic] response, its actual effect, and the intended effect, forms feedback which can be used to modify behavior" (p. 79). Implicitly, the awareness and feedback were the responsibility of the individual working through the process. However, there are a number of examples in the book where feedback is offered by teachers and students alike over role play exercises and students sharing personal experiences they were going through at the time.

'What?' for Sensing out the difference between response, actual effect, and intended effect [remember, based on a personal goal]; 'So What?' for Transforming that information into immediate relevant patterns of meaning [awareness and feedback - did that meet the goal or not]; 'Now What?' for deciding on how to Act on the best alternative and reapply it in other situations [when doing something different to meet a goal is required]" (p. 88).

For those of you familiar with the What Model, you have probably had the realization that its initial intent rings pretty true to how it's still being used today and how else it's used today. Eighteen years after Reach, Touch and Teach was published, the What Model was included in the book, Islands of Healing: A Guide to Adventure Based Counseling, by Schoel, Prouty & Radcliffe. With a reference to Borton, the Model is shared as a "Debriefing sequence" for adventure-based experiential group work. After an adventurous experience, a group can use the What? So What? Now What? sequence to comfortably think about what happened during the experience and eventually get to the "nub of the experience" and use the insights for future interactions or change.

Since, Islands of Healing, the What Model continues to make its way into the reflection and processing experiences of many different groups. It has also been combined with other Models to emphasize (and even simplify) the pathways in complex psychological theories (e.g., Ladder of Inference). The good news (still) is, What? So What? and Now What? Model is a useful tool (an information processing model) in any team builders repertoire. And, to know it was designed to help people meet the goals they aspired to, keeps us on track to use it for the same ends.

Keep doing the good work out there!

Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

Would you like a (super) quick email notification when new OTB content (blog post or podcast episode) is available? Fill out the form below and we'll let you know.

I'm not completely sure why, but I connect well with and remember things better in threes. I think it started with collecting objects/props in threes - as activity equipment and juggling tools.

This model (repurposed a bit) comes from the book, Teaching Online: A Practical Guide (3rd ed.) by Susan Ko and Steve Rossen (I'm interested in teaching online - especially, learning how to create continuing education online courses for adventure educators). In one of the initial chapters the authors tell us that when teaching online you must continuously review your course design and content, reflect on the effectiveness of the design and content (Is it doing what you want it to do?), and revise the design and content if it's not working for you or your students. I realized right away that this is a nice processing model as well. In my simple world I see processing as a noun - it is a time when the facilitator and participants get together to create a space for talking about recent events. During these spaces we use 'verbs' to consider the impacts of the events: Review - participants simply state what they remember about the current event. I like to ask, "If we were watching a video of the last activity tell me what you would see and hear." Or, "What do you remember seeing and hearing during the last activity?" (Trying to leave out opinion at this stage.) (Note: Roger Greenaway uses the term "reviewing" as the noun for bringing participants together to talk. Check out his comprehensive Reviewing Website on the topic.) Then we can.... Reflect - Here we think and talk about the meaning of what was seen or heard (in most cases, talking about 'events' that are connected to the outcomes programmed for the group). Topics can be participant generated or facilitator generated depending on the kind of program you are working:

Revise - After reflecting we can think and talk about how we might want to change - add behaviors that are missing and try to reduce/eliminate behaviors that are not useful:

This basic approach is not completely novel - it's another version of a large body of work on processing. It's fairly synonymous with the, What? So What? Now What? approach (future OTB blog post). These 3-Rs might be, to some, a clearer way to approach a processing session. What other "simple" models have you used for processing? Please leave us a Comment below.

And More

The original intent of Ko & Rossen is to use the 3-Rs an an evaluation tool for online courses. This applies just as well to evaluating a team building program. Use this model after a program to process with co-facilitators or personally if you just finished a solo lead. It's a 'process' of data collection that can inform your practice and help you learn and grow. As always, we'd love to know what you think. Leave us a Comment.

All the best,

Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

Would you like a (super) quick email notification when new OTB content (blog post or podcast episode) is available? Fill out the form below and we'll let you know.

(This is a 'migration' post - it was first shared at FUNdoing.com. We're moving theory posts from FUNdoing to OnTeamBuilding as a way of organizing content.)

What are your foundational principles of practice (POP)?

In other words, what do you believe to be true when it comes to developing and leading/facilitating adventure-based programs? And, the other question worth exploring (at another time perhaps) is where these beliefs come from? For me, my POPs seem to be revealed, more often than not, when they meet up with other's POPs (I like to call these interactions, POP Parties!!). Where there is diversity there is the opportunity for wonderful dialogue, as we know to be true in this field of Adventure Education (and we know, unfortunately, the opposite is also true). Here's an example of a one of the good POP parties from my past. Organizing my vault of hard-copy treasures from workshops past, I found a handout from a Ph.D. (higher ed faculty member) in the field of recreation who lead a workshop at a state-level Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance conference a while back. The Ph.D. provided a handout of thoughts for us to remember and reflect upon from the presentation. I will take an educated guess that this handout included some of this person's POPs. (I remember the workshop to be full of passionate dialogue - good stuff.) This could be the first in a series of Agree or Disagree posts (if this theme catches on.) I would like to present some of the information provided in the handout and whether I (or my POP) agree with the Ph.D. or if I disagree, and my POP in juxtaposition. Handout: Initiative exercises and activities offer a series of clearly defined problems or tasks to a group that must be solved before an acceptable solution to the challenge may be reached. [Note: This is the first line on the handout.] I Disagree: For me, this statement is too limiting. Using words like, "clearly defined problems," "must be solved," and "acceptable solution" limit my programming opportunities for the opposite. Handout: The problem-oriented approach to learning can be useful in developing each individual's awareness of decision-making, leadership, and obligations and strengths of each member within the group. I Agree: And, useful for developing a lot more pro-social behaviors. I especially like the use of the phrase, "obligation and strengths of each member within the group." I believe, through practice and theory, that the use of adventure education is for social development - I teach my student that we work within the 'social' curriculum realm of education (as opposed to an 'academic' curriculum). Handout: [When programing and facilitating initiatives] select a problem that is suited to the age and physical ability of the group. An older group is easily stunned off by a childish situation, and [an]other group may be quickly frustrated by problems that require physical or mental development beyond their capacities. I Agree: In educational terms this is considered proper scaffolding. We work up from where the students (or participants) are, adding new knowledge and experiences to what they already understand and have done in the past. I like the point included about "physical ability of the group." I've noticed over time (I include myself in this observation) that age-related programming is easier to do up front based on our experiences, but there is little consideration of the physical abilities of the participants - often because we do not have (i.e., did not collect) information about this area until we start working with a group. Being prepared to adjust an activity is a valuable skill for a facilitator to develop. Handout: Situations may arise when a participant will break a ground rule of the challenge. The penalty for such an infraction can be either a time penalty or starting over. Be strict in administering the rules of the problem. If the group suspects that you don't care about following the rules, the problem will resolve into horseplay and become functionally meaningless. I Disagree: If I stick to this practice (safety concerns withstanding) as a hard-and-fast rule in my programming I eliminate the opportunity to learn from "functional meaninglessness." When an outside force is constantly holding a group accountable for their actions, how does the group learn about taking responsibility for themselves - we miss the opportunity to talk about such things. If 'following rules' is an objective the group is with you to practice, then by all means, be the moderator. Stay flexible to other learning opportunities. Handout: As an instructor [facilitator], you [are] obligated, during the problem-solving process, to be silent. I Disagree: [I get the most pushback on this part of my POP.] I believe that there are important learnings to recognize "during" a group process that might be better reflected upon in the moment than after the moment has past. Of course, overdoing this (stepping in) can be counter-productive, so we choose these moments carefully. On a related note, after reading more into John Dewey's work with experiential education, I have come to agree that the facilitator is part of the group (arguably a small part) with experiences that can help the group at strategic points (again, not overdoing this) during their experiences. My reasoning for this part of my POP is about the doors/tools of opportunity. Pointing out that there are, or giving permission to explore, other doors/tools of possibly will help a group to learn about choices when they are "stuck" believing there are none, or very few. In time we hope the group understands they might not be limited to only the doors/tools they can see and feel free to explore (look for) more options. How about you? Are you agreeing or disagreeing here? What is your POP? I hope my point is evident. (But just in case.) It can be good to explore, from time-to-time, your principles of practice. This makes us reflective practitioners - important to meaningful education. Attend or start a POP party. Share your thoughts (you can do it here in the comments area below). Agree, disagree, ponder, question. This dialogue helps us all focus in on what's important to us as educators and how we approach our programming and our groups. And, spend a little time considering where your beliefs come from - like our groups, are we stuck using a tool that might not be the best for the job? Or, are tools other people are using better suited? Who doesn't like a party?! Chris Cavert, Ed. D.

Would you like a (super) quick email notification when new OTB content (blog post or podcast episode) is available? Fill out the form below and we'll let you know.

The Team Wall

The Team Wall 'element' is among the oldest challenges in the history of Ropes/Challenge Courses. Dig back into the early days of Outward Bound in the United States, you'll find the Team Wall as part of the team building that took place before going 'out' on trips. Other historical records show the 'Wall' was repurposed into a team challenge from military obstacle courses of old. Today, Team Walls still stand among a wide range of opinion - "Why are we still using the Wall? What purpose does it have on a course? Is it worth it?"

Is the Wall a low element or a high element? What learning/lessons can we enhance by using the element? Are these learnings worth the risk (perceived and actual)? Should we belay the element or not? Does the element bring a team together or actually separate them? These and other questions about the Wall are commonplace. Where do you stand?

One Educator's (Practitioners) Opinion

I (Chris Cavert) started my career (PA Trained) using the 12-foot Team Wall with no belay. Proper training for spotting was always important - especially watching out for the 'windshield wiper' falls at the sides. What I learned was:

When I became a course manager I learned more about 'best practices' (who remembers the 'Red' booklet?). It came to my attention that there was a limit to where a participant should be above the ground (was this their head, torso, feet - wasn't clear as I recall, and I remember 42 inches??) - basically, if the torso went above the hands of the shortest spotter, the climber should have a harness on and a belay system attached. However, at the time, the Team Wall was the exception.

Then, Ropes/Challenge Course builders began to mitigate the risk - they started building Team Walls with belay systems (shown in the picture above). I saw Walls that were belayed from the ground and some belayed from the top through a GriGri hanging off the belay cable - a facilitator took out the slack in the rope and let the GriGri do the rest.

I liked (still do) the idea of the belay, but I wondered, as I saw these belayed Walls being used, did it change the activity - was it now 'too safe' as the argument about adventure education becoming too safe blossomed. And, looking back, I never witnessed a major 'fall' at this element only major bruises and scrapes getting over the top. Was (is) the element worth it?

Around the time of the new operational dualism - belay or not to belay (that is the questions), which still exists at the time of this writing, I stopped programming the Team Wall. I found many other ways to build team success. However, I still, on occasion, work for course manages who program the Team Wall for clients. If I am contracted to run the Wall, here's how I manage it (cleared by the course manager):

Where do you position yourself around the Team Wall? What are your learning outcomes if you use the Wall? What does the Team Wall do for you that other elements cannot?

Leave us a Comment so we can learn and grow together. Be well... Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

Would you like a (super) quick email notification when new OTB content (blog post or podcast episode) is available? Fill out the form below and we'll let you know.

|

OnTeamBuilding is a forum for like-minded people to share ideas and experiences related to team building. FREE Team Building

Activity Resources OTB FacilitatorDr. Chris Cavert is an educator, author and trainer. His passion is helping team builders learn and grow. Archives

January 2024

|

||||||||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed