|

(About a 24-minute read. This is a migration and updated post. It was initially shared on the FUNdoing.com Blog. We have moved theoretical posts to OnTeamBuilding to organize content.)

The What? & Why? Series is my attempt to document some of the things I think about when programming and leading teambuilding activities. This learning tool is an example of one way to think about leading this particular activity, providing the why underlines some of the purpose behind my choices. Things to ponder.

Have You Ever...stood in a circle with 50 middle school students playing Have You Ever…?

I'm guessing most of you know this classic, "Have You Ever...?" icebreaker activity (Rohnke, 1988 & 2004) - I'm sure it's been played by millions! Here’s a review. (Of course, skip this part if you don’t need it.) Our group, of 12 to 50 players, form a circle. Each player is standing on a game spot. We (the facilitator) start by standing with the group, part of the circle, so everyone has a spot for a while, as we explain and then play the game with the group. Now we’re going to say something true for us, something we’ve done/experienced. We preface this information with, "Have you ever..." For example, you might say, "Have you ever been to Canada?" (Again, the statement must be true for us.) If anyone in the group (players forming the circle) has been to Canada, they are invited (but not required) to leave their spot and move to another spot that is not directly to their right or left. While this movement is happening everyone wants to go stand on one of the spots left vacant by another player in the circle – during the first three or four rounds there will always be a spot open in the circle – the facilitator is sharing the Have You Ever…? (HYE?) questions to model the process. On the fourth or fifth round, we move our spot to the middle of the circle as described below – we start this new process by asking another HYE? question. When there is a spot in the middle there will be a player left without a spot to stand on within the circle (because, in this game, there is no sharing spots). The player who gets the center spot, is the next person to share a HYE? question from the center of the circle. The moving, getting a spot process ensues after every, HYE? question from the player standing in the middle of the circle. If the player in the middle shares a, HYE? question, and no one moves, they take a bow and ask another question. Remembering the idea is to get players to move - asking questions that are likely to produce movement is a good strategic play (that is, of course, the player wants to get out of the middle). NOTE: Believe it or not, the step-by-step process detailed below takes me about 15 to 20 minutes to lead. It's a lot of writing for 15 minutes, and an interesting process (for me) to go through. Okay, let's get this one started:

What?

(This section describes one way I lead Have You Ever...? What I say and do.)

Why?

(This section is about the Why of what I did throughout the activity. The numbered comments below match up with the numbers from the What?) 1. I like to have participants help me whenever I can - it's a nice social skill to practice (and it saves me time as well). By clumping together, I can hand out five or six game spots to several participants near me so they can also help me hand out spots - or pass along the spots after taking one for themselves. Being together in a "clump" saves us steps and time in the long run. Another option is to set down the game spots in a circle formation before your participants arrive. In my experience, setting up a circle of spots by myself takes more time than getting help. 2. When everyone has a game spot I collect the extras, and then together we form our circle. Doing this together might become our first "problem-solving" activity! I might give a visual image suggestion, like, "We want to form a circle, like a big pizza, or a basketball." Then, I'll ask my group, "Do you like the shape of this circle, or do we want to change it? What do we need to do to change it?" After asking these questions I listen to how participants are communicating with each other - is it positive, constructive, negative, sarcastic, useful? If some coaching is required, I will add some thoughts while we're getting circlized. I also make sure to praise the useful behaviors and positive feedback participants are engaging in and sharing - I'm starting the norming process with the group. I too am working on forming the circle with my group, because I am also standing on a game spot as part of the circle (remember, this version of, "Have you ever..." does not start with someone in the middle of the circle). For this game of "Have you ever..." (HYE?), I think the circle formation works the best. I've tried HYE? in a square, a triangle, and scattered formations (that was interesting). The circle is best for hearing the HYE? questions and a circle provides more space for moving from one spot to another (again, in my experience). (BTW: Playing HYE?, just as an ice breaker, is really interesting from a scattered formation, but it increases the level of risk. So, if you are norming for safety with your group scattered HYE? might be an option so you can talk about it.) 3. In this step, I'm frontloading the idea of choice. Even though we will be discovering things about each other - some similarities and differences - my main facilitated objective is to emphasize the concept of choice and how choice fits into the program we are in together. Some participants might recognize the game once I share the part about saying, "Have you ever..." When participants speak up, sharing they've played before, I often say, "That's great. In a moment you will be able to help me out since you have some experience with this one. For the moment you might notice some differences in the way I play, so please go along with me on this version and have some fun." I use the example of, "...eaten a slice of pepperoni pizza" because I'm pretty sure there are a few people in the group who have done so. I'm choosing to use an example of something that more than a few people have done so I can get some movement when we try. Now, depending on where you are in the world, you might use a different example. If I use something too unique, like, "Have you ever swam with dolphins?" I might not get any movement during my test run - and I want movement for the example. 4. I come back to the idea of choice at this point. I present choice as an invitation - an invitation to move off of their spots or not if they have done the Have you ever...? I know I picked up the idea of choice as an invitation from someone in my past, but I don't remember who. So, thank you - whoever you are! I suppose being "invited" could be seen as someone with power opening the door for others with less power - and an argument to explore at some point. For me, I like being invited. It shows me I'm being recognized, and seen by others. "Chris, I'd like to invite you to my party!" Thanks! I'll be there." It's an opening, a way of thinking that can work for a lot of people. During discussions with more groups than I can remember, participants have told me that they liked the idea of being invited - they felt included and part of the group. 5. By now I want my participants to lock in the directions with practice. I use the example, "Have you ever eaten a slice of pepperoni pizza?" because they've already been thinking about it. It's not something new at this point - in educational thinking, I'm (sort of) reviewing. Participants already thought about my question, and they've probably answered it, in their heads at least. Now, we're moving (literally) to the next part of the learning process. We're adding something to what we know. We've also heard the directions, now we're putting them into action. 6. I choose to move with the pepperoni pizza eaters at this point, and I also keep an eye on the movement of others. Most participants will recognize that they don't have to move quickly because there is a spot for everyone (at this point). However, some energetic players (e.g., younger participants) might choose to move quickly, so I'm watching for safety issues. Now, as the facilitator, you can choose to frontload the practice step by reminding participants they don't have to run - "there is a spot for everyone." If you think your group needs this information, let um have it. By leaving out the safety frontload I get the chance to observe my groups participate in some natural behaviors. They might already have a good sense of how to behave safely - I might not need to bring it up (just yet). After we are all back on our spots, I can ask the question about choices. (This is where we can talk about "safety" choices if they were observed.) During this first bought of choice recognition, I don't push too much. I like to get into more action before digging deeper. So, here I just ask five or six times, "What choices did you have the opportunity to make?" I don't share any of my observations and choice options I know about at this time - I want to give my group the first opportunity to share what they observed and practiced. However, there is one exception. If I observed any safety issues, we will open this discussion and create some norms (rules) for moving (literally) forward. I will often add, at this point, that one of my roles as a facilitator is to monitor safety issues and help the group develop norms and behaviors around safety concerns. 7. We need to move again. Asking my participants if they have participated in a teambuilding program before is one of my favorite questions. It usually (these days) produces lots of movement and it lets me find out if there are those in the group who have not been in a teambuilding program before - I observe this information in the next step. Again, I'm observing my groups for behaviors (e.g., safety) that may need to be addressed right away. In most cases, I stay on my spot so I can watch the movement. If someone (and this happens quite a bit for me) brings up the fact that I didn't move and asks, "You haven't been in a teambuilding program before? (they are ALWAYS watching us!) I share my choice to stay on my spot so I could observe the group in action (another role I have as a facilitator that I might share with my group at this time). In educational terms, I am modeling choice. 8. After this second practice, I add some new information and action. As a way to now recognize others, we have something in common with. I ask participants to raise a hand if they moved to a new spot. Now, we can look around the circle (again, the best formation to see everyone), to see who has been in a teambuilding program before and who has not. We can also see that we have a difference among us - some have, and some have not. (This is where I might find out who is teambuilding for the first time. Why is this important? I might change my language a bit or define more of the terms I use with my participants. This thinking is another topic we can get into at some point.) And, I do like to invite participants to put their hands down when we're done looking around to avoid any discomfort and confusion about when it's time (okay) to put their hands down. ("Have you ever..." been in one of those situations where you weren't sure, then you just put your hand down because others were putting their hands down? Doing what others are doing because you don't know what to do....now that's something to talk about!) 9. Okay. We're now getting the idea, so I want to prepare my participants for a change coming up. I let them know that, after I ask one more "Have you ever..." question, I will be inviting them to ask the questions. In this way, I'm giving participants a heads-up, and some time to think about something they might want to ask. Even though they'll be listening and possibly moving around, they will have some time to think. In educational terms this is called an anticipatory set - I'm setting up my group for something about to happen. Something they can anticipate. The next new thing will not be new - they "knew" it was on the way. This prepares the brain for some action. Along with my next question, there is a chance that I might be the only one who has done the "Have you ever..." (If you've played "Have you ever..." you know that if you ask a question, it must be true for you. I have not shared this rule yet - but it's on the way.) If I don't see anyone else making a move from a spot, I will take one step into the middle and take a bow. Then, step back onto my spot. (Again, another "rule" - invitation - I have yet to share, but it's on the way.) More often than not, since I'm taking a bow, participants will clap for me - it's a pretty common cultural norm. I didn't set up the bow-clap process yet, but if I have the opportunity to demonstrate it, I take it. Again, depending on the question I ask, there will be more, less, or no movement at all. 10. If there was some movement, I ask the movers to raise a hand. Then we all look around to see who we have something in common with. Again, this action is about providing an opportunity to recognize others. If I have a hand up, I recognize that I have something in common with others who have their hand up. I also recognize there are others I might not have something in common with - there are differences in the group. The participants who did not move, and do not have a hand up, can also assume that they have something in common with others in the group - the non-movers. Now, since there is a chance that one or more of the non-movers could have moved but chose not to, I like to make a short point about assumptions. "We can assume we have something in common with others through observation, but how do we know for sure?" This will often produce comments about "talking" to each other, asking questions, and listening. This, more often than not, is part of a teambuilding program - getting to know each other beyond observations and assumptions. 11. After the movement stops, I invite participants to ask a "Have you ever..." question. But, before they start, I share the information (rules) about how the play will continue - the questions have to be something they've done and if no one moves after a question, the asker is invited to step into the circle and take a bow, at which point we will all clap. I also like to add the option of simply waving as well - stepping into the circle and bowing might not be comfortable for everyone. Again, I like to provide choices when possible and give permission to make choices they are comfortable with. The reason I let someone else ask a question after a bow or wave is to save time. In my experience, if I let the same person ask another question, they often have to take time to think of something new, whereas others in the group might already be prepared to ask a question. Depending on my group, I might give the "Rated G" guideline here as well. "Please share 'Have you ever...' questions suitable for a G-rated movie audience." This will often produce some laughter because they know what you're talking about. This is a choice I do take away. Another role I have as a facilitator is to help create an emotionally safe learning environment. If I let my group make choices that make others uncomfortable and unwilling to open up and connect with the group, the learning environment will be altered. This can be tricky, but important to consider. We (us facilitators) are challenged to provide learning experiences that help groups move forward together as a community, not hinder the process. "Guiding" the process with appropriate activities and purposeful language is our responsibility. 12. Okay. Here I ask for someone in the group to share a question and I remind them about the context of the question - it must be something they've done. Some groups I work with naturally raise hands (it is a norm they've adopted) and I'll pick by pointing at them. In other groups, someone will simply speak up before someone else. Depending on your group, you might need to set up the guideline (rule) that you will pick someone who has a hand up - you might need to structure the sharing (you might want to establish this communication norm). This could be a norm that you want to manage or let the group manage. Will they set up the structure or do they want/need you to set it up? A facilitated objective I have at this point is to move "control" of some of the processes to the group - get them talking and interacting as soon as possible. (Note: By this time in the game, we are only about 4 minutes in! Yeah, lots of words and thinking in 4 minutes!) And, even if I could move to a new spot on some of their questions, I usually stay on my spot and watch the interaction in the game. I'm looking for "things" to talk about - things I need to talk about (e.g., safety issues), and things I would like them to recognize (e.g., group behaviors) that I can bring up in a processing discussion. Purposeful observation leads me to more appropriate questions. (Another good blog topic to explore at some point.) 13. When everyone is back on a spot and I notice (I can see and hear) the group may be ready to give me their attention, I ask the players that moved to raise a hand. Then I ask everyone to look around. Again, this time (space) is provided for participants to look around and see others in the group they (may) have something in common with. During these first few movements and the "raise-the-hand" request, I'll point out that those people with hands up are sharing something about themselves and we can assume that they all have something in common (e.g., they've all eaten a slice of pepperoni pizza, or have been part of a teambuilding program before). The participants who did not raise a hand may or may not share something in common (e.g., they didn't do what the asker did), because they could have chosen not to move even if they could have. "As we move forward together in the program, we'll find out more about each other through talking and taking on tasks and challenges." After the first two or three reminders, to look around, I will leave it up to the participants to process the information on their own - we just get into the game and raise a hand if we move. 14. Overall, I have about six participants share a, Have you ever... question to get some good movement and interaction and to notice some commonalities. I don't go on too long at this level because I want to change it up a bit and get back to talking about and experiencing, choice. 15. Before changing the dynamics of the activity I take some time with the group to explore the choices that were made during the last several rounds. It's easy, at this point, to take in a few responses and move on. I like to stick with this "choice thinking" for a while. The first five or six responses are usually easy to come up with, then when it goes quiet (that, quiet discomfort) we often just move right on to the next part of our process. I like the discomfort. In this discomfort, we are also making choices. "Should I say something?" "This is boring, let's move on?" "Oh, maybe there is more we are not seeing. I wonder. Let me think. What else is there?" I believe there is a skill development process that can be experienced and practiced when in quiet discomfort. What skills can we practice? Patience? Cognitive engagement? Managing frustration? Participation? Respect? I believe providing more time to think about more possibilities to one question there is more time to practice community-building behaviors. And providing more time also gets us to deeper thinking and more answers - answers that are often more interesting than our first reactions. During this discussion, I also ask my group what choices they "didn't" make. It's wording that stimulates a different way of thinking. Yes, we can frame choice answers in the positive (so to speak). For example, "I chose to be quiet during the game so I could concentrate more on finding a spot." This could also be worded in this way, "I chose not to talk during the game so I could..." I found this option ("I chose not to...") helps me when I'm working with people (especially young people) working on specific behavior changes. Here is my favorite (true) example, "I chose not to make fun of someone when I felt the urge during the game because I knew I wanted to work on this." Another, very common one I've heard several times is, "I chose not to run to a spot because I know I might hurt someone if I ran into them." Again, it seems some brains are wired to see what was "not" done as opposed to what "was" done. Now, do we direct skill development towards "I chose to..." and away from "I chose not to..."? I don't know if it matters. We'll have to propose this question to others more qualified to answer (e.g., mental health professionals). If you have an idea, please share!! 16. After I point out the fact that everyone had a spot around the circle during the first round of questions, I make the physical move to the center with my spot to show everyone things are about to change. Now, I could simply stay on my spot as part of the circle and explain what is going to happen. It is arguable that by staying as part of the circle I will be able to see everyone while I’m talking – my back will not be turned to anyone in the circle. However, I believe this physical change provides some visual preparation for the change. (And I use a nice loud voice, turn often, and repeat the directions at least a couple of times to get the change across.) 17. By simply moving into the center of the circle there are usually a handful of participants that can figure out what’s ahead. And, by changing the game configuration participants are starting to prepare themselves for something to change. If I sense some strong reactions to this physical change, I might take a brief moment (before I provide details about the change) to check in with my group to find out what emotions are surfacing. Some people have physiological reactions to change that are challenging to manage. “I was comfortable, now I have to do something new. I’d rather stay where I’m comfortable.” This is an example of one type of comment made several times in my experience. Even playing a (seemingly) simple game, change aversion can come up for people. So, I keep myself mindful of reactions during my move to the middle. When I sense I can provide the group with new information I share the change in the game. During the directs to the change, I do say that the person in the center is, “…obligated to ask a, Have you ever… question.” This can be interpreted as not having a choice in the matter. But do they? There is often an assumption of a consequence without checking. I love it when participants ask about the “obligation” when left in the center. “Well, what choices do you have? Do you have to move?” On more than one occasion, I’ve been involved in a conversation about obligation. Even though a participant does not want to be caught in the middle (they don’t want to be “on the spot”), they still feel obligated to move if the question is true for them. The ensuing behaviors related to avoiding getting caught in the middle tend to be on the assertive side and have caused uncomfortable emotions, reactions, and even consequences. Again, so much can happen in a “simple” game if one pays attention. And, it doesn’t have to take a lot of time to share insights, feelings, and feedback. 18. Before playing the new version of, Have you ever… we take some time to look at the changes ahead and possible choices we have moving forward. Again, what we’ll be choosing to do and what might we choose NOT to do? I also slip in some possible norming behaviors, “How do we want to play during this part?” There are usually some warnings related to increased movement (speed) that might show up and suggestions as to what behaviors might be considered during play. I don’t push this question too much; I just like to introduce the idea of considering how we want to BE together. I will continue with norming discussions later if it’s within the scope of the program goals. 19. Now we get into the new version of the game. After each question, we raise our hands and recognize similarities. I also choose to stay on my spot (for the most part) and observe the behaviors of my group in play. (What’s that quote? You can learn more about people in an hour of play than a day of conversation – something like that.) First and foremost, I’m looking for safety concerns and I address this right away. I will push safety-related norms if needed and hold my group to these norms. I’m also looking and listening for (and at) the behaviors I see and hear. I want to start getting a picture of the individuals in the group and the group as a whole. How are they playing together? Are players exhibiting more individual (selfish) behaviors or group (thinking of others) behaviors? Are players asking for help? Are players talkative or quiet? These observations, prompts, and behavior data will help me adjust the activities ahead (if needed) and help me frame questions during processing sessions that are related to what’s happening (as opposed to being related to program objectives that might not be relevant to the group at the time). 20. I wove the issue about safety concerns above – if I see something, I say something. There have been times when I explored the choices made around unsafe behavior. Excitement and high-energy individuals often “blame” the context of the game for their behaviors – “Well, you didn’t say we couldn’t run.” “I didn’t want to lose (i.e., be in the middle), so I made every effort to get to a spot.” Lots of great opportunities to discuss group interaction, behaviors, and norms. And why certain behaviors are more acceptable within a group than others. 21. After about six to eight questions from participants, I stop the activity to readdress our choices one more time. During this third round of choice thinking, I often hear more insightful responses. The group has practice and experience with the question. They are ready to add more to their answers – and expand their thinking. At this point, I will also share some of the observations I made related to choices being made if the participants do not bring up what I’m thinking about. I do like to check in with participants (in general) about what I saw. Like, “Why do you think some players chose to move quickly to an open spot? Did anyone notice this?” “Why do you think some players offered help during the game and others did not? What helpful behaviors did you notice during the game?” “Why might it be difficult for someone to come up with a, Have you ever… question when they ended up in the middle? What would this be like for you if this happened?” My general approach is meant to build some empathy for some of the behaviors we might see within a group and to open the door to developing some norms around how we want to be together. It’s an opportunity to recognize what’s going on, even if everyone does not see what is going on. Playing and observing are difficult to do at the same time – a good reason to have a facilitator in the group. 22. At this point I want to frontload some of the possible experiences ahead. If (and more often than not) there are participants who have been in teambuilding programs before, I ask them what choices they’ve made in the past during similar programs – I like to get them talking first. Then, I can add to the conversation with some of my experiences. Again, in educational terms, I’m providing an anticipatory set – things people will (or might be) faced with in everyday life. Maybe I’m planting seeds? Maybe I’m “setting” the group (and participants) up for a predetermined outcome? As I see it, with the time I have, it’s a way for me to get closer to desired outcomes. If you have more time (e.g., working with students over the school year), you can do less frontloading and provide more exploration and discovery. Letting my group know there will be lots of choices ahead is the intent of this final look at choice. 23. My caveat – my philosophy about choice (developed during my work with “at-risk” youth populations). I am partially responsible (my participants share in this responsibility) for my group's wellbeing. I need to know where everyone is at all times. Yes, at ALL TIMES. The choice to “disappear” is not an option for my participants. Now, if I relinquish my responsibility to another responsible party (e.g., a teacher or chaperone with the group), then the participant (or participants) is no longer my responsibility. So, I share my expectations about this choice right away. As you see it’s worded that someone can step away from the group when needed (and it can be needed), but I need to have everyone in my sights. And I word it as “helping me” with this. Most of us are very willing to help someone when asked respectfully and with reason. There might be some questions about this and even pushback on not having the choice to walk away, out of sight. But I respectfully make it clear that, as in life, there are often limits to our choices. 24. Now we need the rally cry. I want to ignite a little energy to move forward. I’m always excited to get into the program after a good foundation and understanding (hopefully) of the choices ahead. As we move forward together, choice-thinking conversations continue since we’ve laid the groundwork for thinking about choice on purpose.

As you can see, a lot of thinking can go into one simple activity. My purpose here, again, is to simply share (in a long-form way), what I do and why I do it – just one way to approach group interactions. Maybe, just maybe, it's a good idea, from time to time, to look at our 'why' so we don't lose track of our purpose.

I'd love to get your thoughts. Leave us a Comment. All the best, Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

0 Comments

(About a 12-minute read – and lots of exploring when you have the time.)

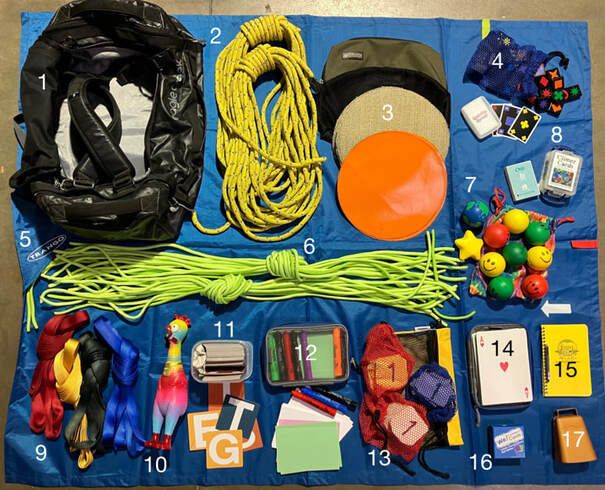

My OnTeamBuilding year-end post is inspired by Matt Mullenweg (with a heads up from Tim Farriss) who shares “What’s in My Bag, 2023” – his travel tech and personal comforts. Matt is a founding developer of WordPress.

This is the teambuilding gear (kit) I used for most of my programs in 2023. I worked out of my onsite housing in Ohio, programming with this equipment, then putting the kit on my back and walking out the door to programs (sometimes a quick car trip to our second site). During the last part of the year this kit stayed in my car traveling with me to the handful of programs I did in Colorado. Karl Rohnke often recommended to his training groups (I witnessed this more than a dozen times), “Find ten good [teambuilding] activities that you can use with any group and you’re good to go.” Early on in my career I didn’t buy into this idea – I loved my 100+ list of activities I curated over the years. However, year after year I’m finding myself programming with fewer activities – I’ve found activities I can adjust for almost any group to practice the most popular ‘concepts’ (outcomes) requested by them (e.g., teamwork, leadership, trust, collaboration and problem-solving). To be fully transparent, I have at least 20 activities at the top of my ‘versatile’ list currently. Maybe it will get to ten at some point.

One final piece of transparency. The gear in my kit can cover about 80% of what I program with up to 24 participants of middle school age and older. I still love the ‘one-off’ activities that help me spice things up or the ones that are ‘perfect’ for the program outcomes. After the numbered list, I’ve added some of my favorite gear off the shelf.

This gear works for me at this time. Sixteen pounds of ‘stuff’ (actual weight) can go a long way done the teambuilding road! What gear works for your top 20? Let us know in the Comments. Our 2024 kits might include some changes!

This list includes links to gear resources and some activities found on the FUNdoing and OnTeamBuilding blog sites. Let me know if you have any questions. (Please let me know if a link is broken. I've checked them all, but you never know. Thanks.)

1. Eagle Creek Cargo Hauler 60L. Updated look, still the same size and features – my favorites: U-shaped zipper opening to main compartment, two end compartments, and removable backpack straps. 2. Two 50-foot activity ropes. Use for boundary lines and activities like Rope Shapes and Group Jump. 3. Activity Spots (in a zipper bag). I use ‘Shelf Cabinet Liner’ cut into 12 by 12-inch circles or squares – light weight and non-skid. (FYI: I learned in my 50s, ‘spots’ don’t have to be round! Life is short, cut squares.) I also carry six vinal spots I picked up years ago. They are made from scrap vinyl awning material (gifted to me by Jim Cain). There are times when I need a different color to signify specific places in an activity, for example, Corner-to-Corner (One of my Top 20 found in Portable Teambuilding Activities) or the ‘Question’ spot in Have You Ever. Any ‘other’ colored spot works – there are a few Shelf Liner colors to choose from. 4. Qwirkle Pieces or Cards This is a ‘one-off’ the shelf that stayed in my kit all year. The square game pieces are my favorite for What’s Missing? and I use the Qwirkle Rummy cards (HERE at Mindware) with the ‘dots’ if there is color-blind diversity in the group. What’s Missing is a great communication, mental model activity I use with almost every program to warm up the problem-solving parts of the brain. 5. Trango Rope Tarp from REI. Protects my gear from the dirt and rain. When I take stuff out of my kit to prep for use, I love a good tarp. And when it start to rain I can quickly cover up the gear for short-term protection. 6. 24 Buddy Ropes, each 5-feet long, ¼-inch diameter from Atwood Rope. For years I carried around 5-foot lengths of P-Cord (and I still do in my light-weight kit), but when I found this ¼-inch rope I switched. It’s a bit bulkier, but the feel of it for activity use and for knot tying is worth it. (NOTE: I did invest in a hot knife to cut rope since I cut a lot of rope. P-Cord is easier to cut by hand and burn with a lighter. The ¼-inch rope takes more time to cut and burn by hand.) Lots to do with Buddy Ropes, especially teaching knots – don’t forget that learning a new skill is all about problem-solving. Add Buddy Ropes to the Human Knot with larger groups and to ‘open’ things up a bit. Then try Objectable Human Knot for an advanced challenge. 7. Tossables – I carry 10 soft lightweight tossables for all sorts of activities. Every Other Group Juggle was my favorite variation in 2023 (the post includes links to other Group Juggles). Years ago, I was able to find the red, yellow, and green tossables (HERE) to use for the Traffic Light Colors (a.k.a., Stop 'N Go from Brain Brolin) norm-setting and processing activities. 8. Image Cards – I carry Chiji Cards and Climer Cards (I’m excited to add the Climer Cards 2 deck in 2024). Most of the activities I lead with image cards come from The Chiji Guidebook. The new ones I’ve developed over the years can be found at the FUNdoing Blog – just search Image Cards. Some favorites: That Person Over There Stories and Image Perspectives highlighting diversity. 9. Webbing (Raccoon) Circles – I carry four 15-foot lengths of 1-inch tubular webbing. The Revised Book of Raccoon Circles is my go-to collection. Grand Prix Racing is a fun energizer to open an engaging session with webbing circles. Check out Jim Cain’s free Raccoon Circle Handout for a great collection of activities. 10. Noisy Rubber Chicken – What is a teambuilding kit without a noisy toy of some kind. And, as I was told when I first started in this field, “You gotta have a rubber chicken!” I mainly use it as a Group Juggle addition, it gets some good reactions. The chicken also serves as a group ‘mascot’ from time to time. It’s something the group is responsible for. And it does add some ‘Fun Factor’ to the adventures. I found my small RC at the Scheels in Colorado Springs (they have a ‘jumbo’ size online). 11. CrowdWord Cards – I like the versatility of large letter tiles. I was a big fan of Jumbo Bananagrams for years, but we can’t get them any longer. Thank goodness for CrowdWords. There are 26 activities in the manual, Doing A lot with a Little (at the link) and lots of ‘letter tile’ ideas at FUNdoing (search Jumbo Bananagrams and CrowdWords). Here are two of my favorites: Word Building and Take Two. NOTE: I have one of the original CrowdWord sets, unlaminated. They are now laminated. 12. Index Cards and Markers – Lots to do with index cards and markers. I carry about 12 'Flip Chart' markers and a pack of 100 four-color index cards and about 50 white index cards. With just about every program I facilitate, I have my participants make ‘Name Cards.’ I can use them as activity props and I can use them to practice names after I collect them post-activity. One of my Top 20 is Name Card Exchange (this is a long-form post if you’re interested in a deep dive). Then there is Jim Cain's book Teambuilding with Index Cards I pull from. 13. Numbered Spots – I carry three sets of numbered spots, from 1 to 25, in three different colors. Search ‘Livestock Tags’ for a variety of sizes and shapes. They are a bit pricey, but I’ve had them now for over 20 years, so they have earned their place in all my kits. I like programming Key Punch with multiple groups playing at the same time (a Top 20 activity for me). I use the two ropes and three webbings tied together to make three boundary areas for the ‘keys’ and one webbing for the starting line. I use Key Pad Express and Thread the Needle with smaller groups and combine the numbered spots with cups for Cup Switch found in Cup It Up. (See Tube Switch for the original version). 14. Jumbo Playing Cards – Probably the most versatile prop in the teambuilding world. The best collection of activities is in Playing with a Full Deck by Michelle Cummings. And this year I was reintroduced to Michelle's Stack the Deck cards – a combination of standard playing cards on one side and Ice Breaker Questions, Debriefing Images and the activity '52 Card Pick Up' on the other side of the cards. This will be my 'playing card' deck of choice for 2024. Here are some go-tos from the FUNdoing blog: Pressure Play Too, Quad Team Flip and Find (new in 2023), and Quadistictions (along with Chiji Cards). Search 'Playing Cards' and the FUNdoing Blog for more. 15. Weatherproof Notebook and ‘Space’ Pen – A few years ago I made this weatherproof notebook and ‘space’ pen part of my kit. I went through too many instances where the ‘old’ paper pocket spiral notebook and Bic pen failed me. After the change, never a problem. I like to jot notes about group observations, quick game Tweaks, and questions I want to ask the group. Sometimes I’ll need to diagram something for a visual aid (e.g., a five-pointed star). I also take self-reflection and (if I’m working with one) facilitation-team notes about programs. Caveat: I write out my program activity sequence on large index cards for quick access. I record my final program sequence in my Programs folder on my computer. I do this to save room in my weatherproof notebook for ‘in time’ information (these notebooks are an investment). And the 'Space' pen? Worth every penny. It's compact design fits nicely in any pocket and it just writes ALL THE TIME, in any weather. Invest in a spare ink cartridge right away since it's not possible to see when the ink is getting low. Search: ‘Rite in the Rain Journal’ and ‘Space Pen’ for purchase site options. 16: We! Connect Cards – This is another 'one off' the shelf, but they are just the best, compact set of icebreaker question cards I’ve ever used. So, I keep them with me. (Transparency: I keep my kit WE Cards in a zipper pouch without the box. The box was just better for the picture.) And Chad Littlefield's stuff is just GOOD! I plan to add Chad's We! Engage Cards to my kit in 2024 for something new to explore. 17: Large Cow Bell – You know what they say, “You can never get enough Cow Bell!” (In truth, you actually can get enough.) I use my bell to get my group’s attention. I combine this ‘noise’ with a few other attention-getters to save my voice over a long program day. Again, I don’t use it all the time because it can be irritating when overutilized (a great metaphor to work with!) Search ‘Livestock Bell’ for lots of choices. Here are several resources I used on a regular basis in 2023 for the other 20% of my programming:

And thank you for all the important work you did in 2023. Keep it going, we need it more than ever. I wish you all the best in 2024! Keep me posted…. Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

(About a 12-minute read and a few minutes for the Practice session.)

I’ve been working on editing activity descriptions for an organization's database. Each activity includes some “possible reflection questions.” Anyone familiar with asking educationally-minded questions would see both closed-ended and open-ended questions in the mix.

Over the years, my perspective on these two forms of questioning has been molded into the belief that one is not better than the other (contrary to some of the training philosophies I’ve been exposed to throughout my career). It comes down to purpose. When you plan for using a questioning method and it works, it serves, well, the purpose. If unsuccessful, you consider (reflect upon) how you could use the method better or what could serve you better next time and try that. As Maya Angelou tells us, “Do the best you can until you know better. Then, when you know better, do better.” Working through the database of activities I’ve been adjusting some of the reflection questions to (in my experience and opinion) open up more/deeper conversations. I started saving some examples of the changes I was making to share my thinking with other educationally-minded questioners like you. Before we get to the examples, I want to share some information about closed-ended and open-ended questioning. Personally, I want to reemphasize, that one form is not better than the other. These two methods are tools. And, like literal tools, each has specialized (intended) applications. I flat head screwdriver turns, in or out, flat-slotted screws. A hammer is intended to hammer in or take out nails. Yes, both can be used to do other things but were initially designed for a particular purpose. Just like questioning. For some additional perspective, I asked ChatGPT (another tool with an intended purpose): What would you tell someone who wanted to know the value of both closed-ended questioning and open-ended questioning? Here are a few replies that support our exploration (use my prompt to see all the responses):

Both closed-ended and open-ended questioning have their own merits and are valuable in different contexts.

Closed-Ended Questioning

Open-Ended Questioning

Balancing the Two

Here are some question examples I saved under a few categories – each explained below. The final ‘Practice’ category is for you to reshape the questions in order to open up some deeper conversations (on purpose).

Closed-ended adjusted to Open-ended Question These are examples of adjustments I made to closed-ended questions – I would use the open-ended questions to get the same information with more conversation. C: Did anything surprise you about this activity? O: What surprised you during the activity? C: Was it difficult to remember the names of the opposing team? O: What makes it difficult to remember people’s names? C: Does this activity remind you of anything in your everyday life? O: What things in your everyday life does this activity remind you of? C: Did everyone make it to their final destination? O: What did it take from everyone to make it to your destination safely? C: What was your reaction when we switched to a new tangle of rope? O: When you found out you had to untangle someone else’s knot, what came to mind for you? C: How would it feel to constantly be cleaning up someone else’s mess? O: What are some of the choices we can make when we find someone else’s mess? Which one of these choices is common for you? Which one of these choices would be your preference? C: Did you ever help a person in need of a ship? [A place to stand safely.] O: Think about this first before answering – did you see someone in need? What did you do about it? Where do you believe you picked up this trait? Why do you use this trait? C: Think about how the group communicated during the activity. Do you see any connections to communication trends on your team? O: Think about how your team communicated during the activity. What connections do you see to the communication that takes place in your everyday lives? C: How important was empathy in this activity? O: What is your understanding of empathy? How does empathy fit into an activity like this? (What did it look like, or sound like during the activity? What are some other ways we could have been more empathetic? What does empathy look like in some of your other teams?) C: What behaviours did you notice going on during the activity? O: Describe some of the things people were doing during the activity that made you uncomfortable. What were people doing to make you feel comfortable? C: How important was trust in this activity? Who did you have to trust? O: In what ways did you have to trust your partner? What did you do to maintain the trust with your partner? What did you do to diminish trust with your partner? What commitment can you make with the whole group to build trust? C: How did it feel to be holding a lower-value card? O: When you had a pretty good idea about the value of your card, what conversation were you having in your head? [Self-talk objective.] C: How did you get into your groups? O: What did it take from everyone to get into your smaller groups?

Closed & Why?

It’s common to follow up closed-ended questions with an open “Why?” Here are some adjustments to using an open question right off the bat. C: Is it easy or hard to talk about how you’re feeling? Why? O: What are the things that make it easy for us to talk about our emotions? What are the things that make it challenging for us to talk about our emotions? C: Did your thinking change throughout the activity? Why? O: How did your thinking have to change in order to achieve the goal? C: Were you worried about slowing the group down when the hoop came to you? Why or why not? O: What concerns did you have during the activity? Where do you believe these concerns come from? C: Did your process change at all? Why? O: What changes took place during your transition from one side of the tarp to the other? In your opinion, why did these changes occur? C: Are there things you would change about the way you treat other people? Why? O: From this point on, what would you like to change about the way you treat others? C: Did anything change in how you communicated? Why? O: In what ways did your communication change during the activity? What caused these changes?

Closed with Follow-up to Open

Use closed-ended questions to “gather data” and then follow up with an open question to dive deeper. C to O: What were some feelings you experienced during this activity? How did any of these feelings influence your participation in the challenge? C to O: Did you feel uncomfortable at any time during the activity? What did you do about it? What are some other ways we can respond when we’re feeling uncomfortable? C to O: Raise your hand if this was your first experience with a Lycra Tube. When we’re trying something for the first time, what do we want to keep in mind? C to O: How were you being treated during the mingle? What did you do about it? What would you like to do about it in the future? C to O: What were some feelings you experienced during this activity? How did any of these feelings influence your participation in the challenge?

Open to Closed

How about flipping the script? Start with an open-ended question, then finish with a closed to emphasize a final position. C: Was your group successful? O to C: How did you all define ‘success’ for this activity? Based on this definition, were you successful? C: Were everyone’s ideas heard? O to C: Describe the process you had for sharing ideas. Were everyone’s ideas heard? How do you know? O: How did the group agree to try an idea? O to C: Describe how the group agreed to try an idea. Is this the way you want to continue making decisions? How would you like to make decisions in the future? C: Did anyone feel left out? O: What feelings did you experience during the different rounds? Were the feelings the same for each round or did they change? What influenced the change?

Practice Questions

How would you adjust each closed-ended question below to dive a little deeper?

There are many ways to form and use questions in educational settings. Have a purpose. Reflect on the efficacy. Keep doing what works for you, change it up if needed. When we know better, we can do better. Keep doing the good work out there. We need you! Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

(About a 20-minute read. This is a migration and updated post. It was initially shared at the FUNdoing.com Blog. We are moving theoretical posts to OnTeamBuilding to organize content.)

The What? & Why? Series is my attempt to document some of the things I think about when programming and leading teambuilding activities. This learning tool is an example of one way to think about leading this particular activity, providing the why underlines some of the purpose behind my choices. Things to ponder.

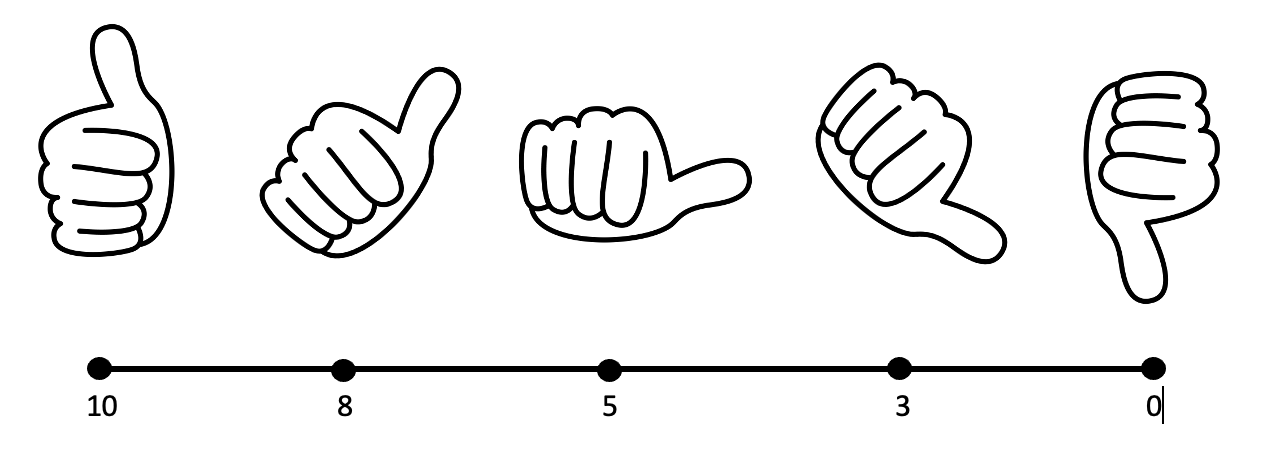

Across Toss is a true mash up of influences. Mainly, All Catch (detailed in the footnote below) from Karl Rohnke's, The Bottomless Bag (1988), Falling Star, in my book, Portable Teambuilding Activities (inspired by another Rohnke activity called 7-Up), the phrase (and philosophy) "Keep your agreements!" from my friend West and the way I use the activity (I call) Have You Seen My Lunch, playing it the way it was described to me by Scott Goldsmith (author of Experiential Activities for Enhancing Emotional Intelligence) when he uses it to talk about agreements - how we make, keep and break them. My initial attempt at Across Toss was with a group of 6th & 7th graders. I wanted to weave in the idea of making agreements (as a way to develop some norms together), understanding agreements, keeping agreements, and sharing voice or 'speaking up' as I framed it. (There can also be some work on how we manage and treat mistakes within the group, but this was a secondary focus for me.) In this What? & Why? format, I'll break down the activity step-by-step (What?) and then tell you my thinking behind each step (Why?). Reality Check: In real time, I spent about 15 minutes on this Across Toss of the 90-minute team building activity portion of the program. After the team building three more hours were spent on the high course where 'making agreements' carried over to enhance the learning points - mainly, making and keeping agreements. Have you ever considered how much (thinking, decision-making, choice) goes into facilitating a 15-minute activity? Here's what it's like for me at least: What? (This section is about What I did, and will generally do, when leading Across Toss with Agreements.) 1. I have a game spot and two safe tossables for each participant ready to go. (My tossables were stress balls, a squeaky penguin and some inflatable orbs a little bigger than a softball.) 2. I gave everyone a game spot and asked them to circle up - about a one-arm distance apart from each other - and then instructed them to stand on their spot. 3. There were eight participants in the group, including me (I played as well). I chose to start with three tossables. I handed out the tossables to three different people. 4. I frontloaded the activity with this information: "This activity is about making agreements with your group members. For example, one will be with the person who agrees to catch the object you have to toss - when you have an object to toss. Another one I'm going to ask you to make is to agree to speak up if you are unsure of anything during the activity." 5. I interject here: "Throughout our program together, I'm going to be asking you to make other kinds of agreements. We'll have the opportunity to discuss the agreements before you commit to them. And maybe there will be some agreements you can't make - and that's okay. We will work through this as well." 6. I go on to ask for one agreement: "At this time, can you all agree to speak up any time you are unsure about something during the activity? This might be difficult to do, but I'm asking you to try. Can I get a thumbs up if you agree?" If there are any thumbs down, we talk through the concerns - I emphasize we are simply going to try and do our best to keep our agreements. 7. I provide the challenge at this point: "Here's how the activity works. As a group, our objective is to catch as many objects as we can - twice in a row. I'll explain this in a moment. We play the game in a series of Rounds. For Round 1 we have three objects to toss - hold up your object if you have one in your hand. Cool, thanks. Each Round will have at least two toss attempts, maybe more. I, for now, will begin each toss attempt by saying, 1, 2, 3, toss. On the word 'toss' everyone must toss their object to someone else in the group - you are not allowed to toss an object to yourself. If all the objects are caught on this first toss, we go for another toss with these three objects. I will say again, 1, 2, 3, toss. All objects must be tossed at the same time - objects can't be tossed to yourself AND you may not toss it back to the person who just tossed it to you. Now, if we catch all the objects this second time, we will add another object to the challenge - this is what I mean by catching the objects in play twice in a row. When we add an object, we move into the next Round. Again, the challenge is to see how many objects we can catch twice in a row. So, the more Rounds we play, the more objects we have caught. If an object drops to the ground after a toss, we simply try again - starting with zero catches. There might be time to discuss some questions after a drop: If we view a drop as a mistake, will it be okay to make a mistake during the activity? Who's made a mistake before? How do you like to be treated after making a mistake? How do you treat yourself after making a mistake? How do we want to treat ourselves and each other after making a mistake? Again, if a drop happens, we get to try again. The bottom line is that we will play each Round until we can catch the object in play twice in a row."ttempt at

NOTE: During the first attempt at Across Toss, I did take a little time to 'check in' on (process) the drops. I asked if they could tell me why an object dropped and what could be done to prevent this type of drop in the future - again, just a quick check.

8. I let the everyone know, "I am part of the group for this activity, so I am available to make an agreement." 9. At this point I ask if there are any questions about the challenge or directions. 10. It's time to toss. "Okay, let's give this a try. Everyone with an object, please make an agreement with someone in the group that will try to catch your toss. Then, you all let me know when you are ready for the toss." 11. I confirm, "Is everyone ready? Are you sure? Tossers, who is your agreement with?" I have them each point out who they have an agreement with. "Okay, here we go. 1, 2, 3, toss." In this Round I am calling the toss, until the group catches the objects twice in a row. 12. When the group is successful, we celebrate with hoots and claps!! 13. Here we discuss: "Let's check in - what agreements did you make so far? Were you able to keep your agreements? What happened if an agreement was not kept? Are there any questions or concerns about our agreements so far?" 14. At this point, I ask everyone to make another agreement. "Before moving on, I'd like to ask you to make another agreement with me and the group. I would like you to agree to speak your truth as we move on through the activity. There might be times when your truth is different than those of other group members - so it might be difficult to speak your truth, but I'm asking you to try. Do you have any questions about what I'm asking? Please give me a thumbs up if you can agree to try and speak your truth." 15. After our new agreement I introduce another object. I ask, "Do you all want to add in another object, all the same rules apply, or do you believe three objects is the best we can do at this time? What is your truth on this?" After some discussion we go to the next Round or decide together to stop and move on to another activity. If the group decides to move on to the next activity, we process our Across Toss experience (see below, Step 17) before moving on. 16. Playing the next Rounds: Rounds continue until the group 'agrees' that they have done the best they can do, at that time, and want to move to another activity. For each Round the rules are the same - when a player has an object (or two) to toss, they make an agreement with a catcher (or catchers). Then, everyone tosses on the word 'toss.' After the first Round the group decides who will count down the toss ("1, 2, 3, toss.") The group makes tosses until they can catch the objects twice in a row OR they decide, during a Round, they have achieved their best effort. 17. Processing Across Toss: After the decided end of the activity, I focused on one area of understanding - making and keeping agreements (the purpose of this specific set up). Even though I did (and will in the future) bring up some other learning moments (like, how we plan to treat each other when a mistake is made and preventing future drops - problem solving), I focused on the one topic for the processing take aways. Here are some of the questions to ask:

Why?

(In this section I give you the Why behind what I did for each step.) 1. I like using games spots if I have them - they provide clear information about where to stand when I want to keep this a constant. For Across Toss you don't need game spots. I chose to use a variety of tossable objects because I like the visual diversity and it provides an opportunity for participants to speak their truth. For example, in this first attempt at Across Toss one of the participants (during Round 4 I think) did ask if someone else would be willing to make an agreement with her tosser because the ball he had was small (stress ball) and hard to catch. To solve this, someone in the group traded objects with the tosser so he could have a larger object - the catcher was then comfortable enough to make an agreement with her tosser. Good Stuff!! 2. The circle with one-arm spacing is good, in my opinion, for tossing-types of activities. Players are not tossing over anyone. I decided if they asked to resize the circle I would let them, but if they ask to change the shape of their formation, I would not let them. In my thinking, I took away some problem-solving options (not an objective I was working on at the time, to focus on the topic of making agreements. 3. Starting with three objects saved some time - we could have started with one object, progressing from there. But I believed the group could handle three at the get-go. In a different situation I would go up to half the group starting out with an object - half are catching, and half are tossing. However, I wanted to have a couple Rounds of practice and confidence building before someone in the group had to both toss and catch. And I included myself in the action because this one seemed easy to observe while playing due to the controlled nature of tosses. I felt confident that I could, toss, catch and observe all at the same time. 4. Here I simply told them about what we would be working on during the activity so they could anticipate (a bit) what they would be talking about (known as frontloading the experience) during and after the experience. This can be considered the 'WHY they are doing this' part of the introduction. Providing some examples jump-starts the brain towards what to expect. I also knew that this middle school age group would understand what an agreement is so I didn't go into defining an agreement - but this could be done if needed. 5. This 'interjection' is considered framing the experience (different from a frontload). Framing is information about the structure of the program - "Throughout the program I'll be asking you to make other agreements..." Using Across Toss to introduce agreements gives us an experience to go back to during the program when we made new agreements or were still keeping our initial agreements. For example, I used this during the high course part of the day, "Remember during Across Toss I asked you to make the agreement to speak your truth, even if it would be difficult to do? Well, I'm still asking you to keep this agreement - to speak your truth about the Leap of Faith. What is your truth?" (A participant was feeling pressured by a friend to climb the pole, but I could tell he really didn't want to. So, I asked him for his truth.) He chose not to climb and instead, chose to be the anchor for the belay team. Again, good stuff! 6. Here I asked them to make their first agreement. I felt it was a reasonable first step - basically asking them to ask questions if they had them. In my experience, this is an easy agreement to make ("Sure I can ask questions."), AND it can be difficult to keep this agreement ("I'll look stupid to others if I ask this question."). This makes for a good processing question - "How many of you had a question or a concern you wanted to voice, but didn't? Why do you think we hold back questions?" A good thread to tease out. 7. This step is about flushing out the directions. I chose to start out saying the countdown ("1, 2, 3, toss.") so I could model this role. NOTE: In my plan, I was prepared to pass on this role to someone in the group - giving the group more responsibility. However, it didn't feel right relinquishing the role with this particular group. As described (Step 7 above), by all means, pass off this role if it feels right to do so. I didn't (and usually don't) get into super detail with the rules right away, I want to get my groups playing. Playing allows a group the chance to collect some data and then ask better questions. When talking about drops, I don't spend tons of time here either - I don't make a big deal about it. I did tell my group, "...a drop can be seen as a mistake - so how will we treat each other if this happens." We discuss and move on. Again, my focus for the activity was on making agreements. One of the agreements was to TRY and catch a toss - so, essentially, catching was not required, only a try-to-catch. Now, with that said, could there be some embarrassment around not catching? Yes. But a reminder about making the try is what's important. "Did you try? Awesome. Then you kept your agreement. Now, we get to TRY again - we get more practice. Isn't this great?!" 8. Here I remind everyone I get to play as well - I can make agreements with them. I also share that I will not always get to play because my responsibilities will change depending on what we're doing. But, whenever I can, I'll play. I believe 'playing' with the group provides me with the opportunity to build rapport - be a part of the successes and limitations. We can be in it together. And adults are great resources and very willing to make agreements and show (sharing experience) that it's hard for us as well, to keep agreements all the time. For example.... I share stories about myself so my participants will (hopefully) get the scenes that I'm human, just like them. 9. I believe it's always important to provide the group opportunities to ask questions - and this was an agreement I asked them to make. My process is this - after asking if anyone has any questions, I look at everyone in the circle, making eye contact with each person for about three seconds. I go around twice (the second time a bit faster). This allows time for everyone to think about a question they have and then formulate how they want to phrase their question. I find this process produces more interaction from the group - they are more willing to share if they have a little time to think and decide. 10. Here I'm asking them to make their first agreement with someone in the group. I don't tell them how to do this - I want them to figure this part out. And it's not easy for everyone to 'ask' something of another person. This is part of the learning. If a solid agreement isn't made, there is confusion and drops. So, I let this play out on its own. 11. Now, before we tossed, I asked everyone to confirm who they made an agreement with. I want to hold them accountable for at least Round 1. NOTE: During this initial attempt with Across Toss I did not ask for confirmation in the subsequent Rounds - we saw more drops occur than the first Round. And the group did come to realize that without clear agreement drops were more likely. Round 1 only needed two tosses - I believe checking in with their agreements helped. We were able to clear up any misunderstandings before tossing. I facilitated the process. 12. We celebrate after the first Round - I celebrated a bit more than they did, they didn't think it was a big deal, yet. And we did take some time to talk about the importance of celebration and what celebrating can do for motivation. Not a ton of time on this, just planting seeds for later. 13. Here we did a little check in to see where we stood. We had two agreements so far - agreeing to speak up if they had questions or concerns and making agreements between a tosser and a catcher. Then we talked, briefly, about how everyone did with their agreements. After the first successful Round with no drops, everyone felt they kept their agreements. We were feeling good. 14. Before moving into the second Round, I introduced the group to a new process in the challenge. I'm telling them, at this particular time, because this is where it's most relevant. I didn't ask them to make this new agreement right away - they didn't need to at the beginning. So, I saved some time in the beginning. I didn't overload them with information. Give what is needed at the onset and add as you go. At this point they are asked to make another agreement about speaking their truth - even if it's difficult to do. Others might have a different truth. It's about reaching consensus as a group - everyone agreeing to keep going or stop and move on to the next activity. 15. So, when adding one more object to the challenge with each new Round, I asked everyone to speak their truth, whether or not they thought they could be successful - two catches in a row - with another object. Or were they at their best number of objects. 16. In this initial attempt of Across Toss, the group had no issues with adding another object - up to Round 4 where some participants were now tossing and catching objects. There were drops in Rounds 2 and 3, but the group quickly realized their agreements were not always clear, leading to 'mistakes.' they did a good job supporting each other, as well, as they tried again. I facilitated some questions about agreements to help them consider solutions. During Round 4, there were successful catches, but then failed second attempts. After six failed twice-in-a-row attempts, I asked if this was the best they could do at that time. Some were very vocal about staying the course and trying again, other stepped up and spoke their truth, stating they thought this was good enough and they would like to move on to something new. After processing a little around the point of 'making agreements' they all felt they got the message and were ready to move on to something else. I stepped in with processing due to the limited time we had with our team building portion of the program. Another choice I can make in the future is to let the group hash out their truths a bit longer to see if they can come to a decision on their own - keep trying or move on. 17. After deciding to move on we processed for about five minutes. Again, only focusing on agreements - this was the main lesson I wanted to take forward with this group because more agreements were ahead. And we were still going to keep our agreements of asking questions and speaking our truth! Programming Notes: As noted, this was the first time I tried this activity, and it met my expectations - my desired outcome to talk about agreements. Now, I don't know how far a group can get with this one. We were a group of eight and made it to six objects (to Round 4). That was two people tossing and catching. So, what is possible? This has yet to be determined. Let me know how far you get. Footnote: All Catch (original verbatim description) from Karl Rohnke,The Bottomless Bag: The group stands in the jump circle in the center of the gym. Group numbers about 25 and holds 10 balls. When the instructor calls "Throw," all release the balls (volleyball type) up to a height of at least 10 feet. If you throw a ball, you cannot catch a ball. Throws are made only on command. Only catchers have to be in the circle. If a ball touches the floor, it is out of play. When three balls are left, the game is over. Count the number of catches made to establish a score. Have FUN out there my friends! Keep me posted. Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

(About a 7-minute read. The first volume in this 'Skills and Abilities' series is a slightly updated version of an interview I had with John Losey in 2017 - still relevant today. It was originally posted at the FUNdoing blog. We are moving theoretical posts to OnTeamBuilding to organize content.)

After introduction material for John's Growing People Podcast, he dove right into his main question: What are a few vital skills and abilities good facilitators possess?

Don't Take Things Personally In my opinion, the most important ability of a team building educator is referenced by don Miguel Ruiz in, The Four Agreements: A Toltec Wisdom Book - Don't take anything personally.* As a young educator (back in the day), this was not easy - I did take things very personally. I was just trying to help, after all! Luckily, during my first (real) Adventure Education job my new mentor told me that taking things personally - especially when working with at-risk youth, young people struggling to fit in - influences our decision making. They're going to project, they're going to blame me, they're going to make me the bad guy for 'making' them do things [pushing them out of their comfort zone] they don't want to do. Yes, I chose to feel horrible. My mentor noticed I was avoiding learning opportunities, not pushing enough. I was avoiding my own discomfort. I was avoiding the hard work that goes into behavior change. Our job, he said, was to get the kids to do that difficult stuff, to get mad at us, to blame us. Then we could help them understand there are other choices, other ways to respond to discomfort. My mentor's feedback, that moment of learning for me, was very important. It stuck. Not right away, but slowly over time I got better and better at doing the hard work, avoiding my personal suffering. As we dive into team building [and team development], to really help our participants/students to know and 'get' what they have asked us to learn, we need to be able to create experiences where discomfort is going to show up [this is our job!]. Participants may lash out at us. And yes, it's not pleasant. There is a physiological response - we get knotted up inside. It throws us off our game if we let it. So, the practiced ability is to not take it personally. Here's an analogy I use to make the point: As educators we are tasked (hired) to provide our groups with a rollercoaster ride [this, of course, does depend on the kind of program a group is looking for]. We are the operators, we don't get on the ride. We are skilled in setting up the ride, buckling them in, and sending them on their way. This ability to separate ourselves from the group's experiences is not easy, but a vital ability. Maintaining objectivity (disconnection) is essential to noticing the behaviors that arise in our groups and then helping them to discover and internalize their learnings.

Concepts and Behaviors

Another ability, or maybe even more of a skill, is for team building educators to understand the difference between a concept and a behavior. For example, concepts tend to be the typical objectives we get from our clients. They want to work out their challenges with teamwork, communication, trust and/or leadership (to name a few). Specifically, they will tell us they have a hard time communicating with each other, or there is a lack of communication, or they are not listening to each other which is leading to misunderstanding. There is some sort of communication issue. Communication is a concept. What I call a BIG word. To change, or help mitigate a problem concept, we need to identify the behaviors that make up the concept. Here's the analogy I like to use for this idea: Let's grab a jar of peanut butter. It says PEANUT BUTTER real big on the label. This equates to a concept. It's the name for all the stuff inside the jar - peanuts, sugar, salt, preservatives, etc. In our analogy, the 'stuff' equates to behaviors, the things that make up peanut butter. So, if a client wants us to work on improving communication, we need to identify the behaviors involved (the stuff) in communication like intonation, body language, eye contact, turn-taking, repeating what was heard (in active listening), use of words and how many words used, along with the kinds of words used. Identification of behaviors could be done during the pre-assessment (in some cases) or behaviors can be discovered during the program itself. Behaviors are things we can see and hear. When we can point out behaviors within a group, get them to see what they are doing and hear what they saying, we can help them change what isn't working and practice what is. Understanding the behaviors within a concept also helps us choose (plan) activities we know will bring up these behaviors. When we're asked to work on improving communication, we'll choose the activities we know that involve communication between participants. For example, I'll have my group line up alphabetically using verbal communication versus asking them to line up without talking. I'll require five minutes of planning before an activity instead of letting them jump right into it - I'm 'forcing' some communication so we can process how it goes. Ultimately, if participants can learn how to see the behaviors within their group and not just say, "We don't communicate well," they can help each other change the specific behaviors that are not working for them. In my experience it's often just one behavior that needs to change in order to reach the outcome desired.

Asking Tough Questions

Being comfortable (and appropriate) asking tough questions is another important skill and ability of a team building educator. It goes back to not taking things personally. When an educator is ready and willing to work with the resistance that may occur, powerful learning can take place from tough questions. When we're asking questions, we're processing experiences. When I train team builders, I encourage them to find a processing method they are comfortable with - one that can include tough questions. (For example, "I noticed one person in the group did most of the talking throughout the activity, how did this influence the participation of others in the group?") We train on some methods, for example the, What? So What? Now What? and Open to Outcome models. We practice a bit, work on other techniques, and reference even more. I always emphasize that getting comfortable with processing (and asking tough questions) takes time, it's an art. Observe other educators asking questions, get feedback on your processing from experienced team builders, dive into books and online resources for ideas. Mistakes will be made; we'll learn from them and promise to do better next time. Tough questions don't have to be bad experiences with groups when they are woven into a program with positive intent. On that note, it’s important to find out (e.g., pre-assessment) how 'deep' a group wants to go during a program. Don't take them down a path they are not willing to travel. Bringing up tough questions during a team development program is more common than asking tough questions during a team bonding program. Find out how much work a group is willing to put in and temper your questions to their desired outcomes.

The most important thing to remember is if you're willing to put in the time and effort at developing your skills and abilities as a team building educator, improvement is bound to take place. Be patient. Anything worth attaining takes time.

* The other three agreements shared by Ruiz (very relevant to good educators): Be Implacable with Your Word; Don't Make Assumptions; Always Do Your Best. All the best, Chris Cavert, Ed.D.

My good friend John Losey shared a piece in one of his recent IntoWisdom monthly newsletters (sign up HERE to follow John's thought provoking work). He let me repost here at OnTeamBuilding - it fits in well with our ongoing conversations. Even though 'novel' (or 'Cool') activities are enticing, John reminds us to keep our focus on the outcomes, the purpose of what the activities are for - to learn and grow together. It's about what happens within the group during the activity. It's not about the activity itself.

Avoiding the Novelty Trap by John Losey